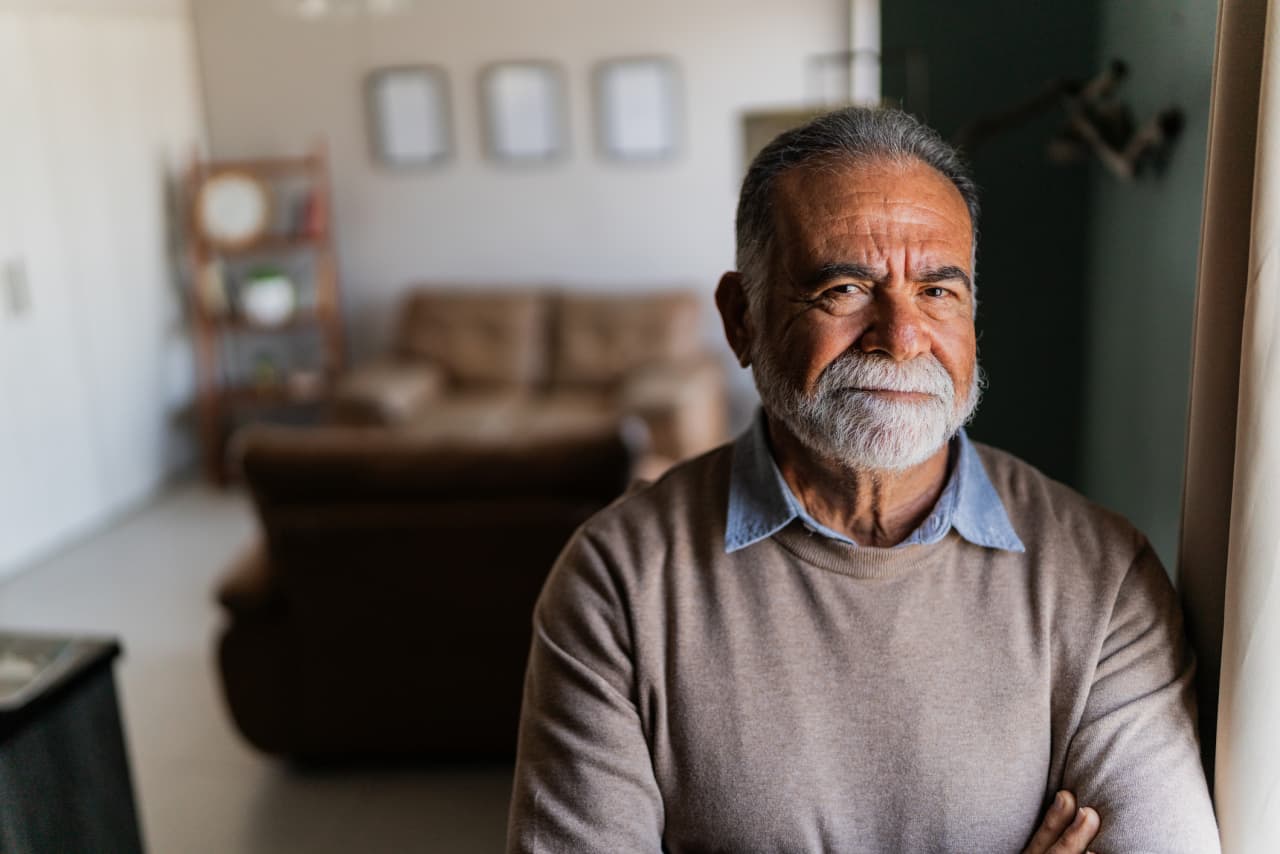

‘He’s 100 Years Behind the Times’: Malaysia’s Ex-PM Mahathir Mohamad on Trump and Today’s World

The 99-year-old ex-Prime Minister dished about the disruptive U.S. President, Vladimir Putin, and global affairs, in an exclusive interview.

During his many decades in politics, Mahathir bin Mohamad has been accused of many things. Laziness was never one. Even today, at a venerable 99 years of age, Malaysia’s longest-serving Prime Minister, who left his second stint in office in 2020, arrives at his desk by 8:45 a.m. and rarely leaves before 5 p.m., holding meetings, reading policy papers, and commenting on domestic and world affairs via his blog and social media. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“I always advise people when they age, they should be active,” Mahathir tells TIME in his Kuala Lumpur office. “Keep yourself busy and your brain busy. If they go to sleep, they lose their power.”

Mahathir has been synonymous with power for as long as anyone can remember. Born to a working-class family in the town of Alor Setar by the Thai border of what was then British-ruled Malaya, he won a scholarship to medical school in Singapore and practiced as a doctor for 20 years while slowly climbing the political ladder. After becoming Malaysia’s fourth Prime Minister in 1981, he ruled the Southeast Asian nation for 22 years until he stepped down in 2003, only to regain the top job in 2018 at the age of 92 with his country embroiled in what was the world’s largest corruption scandal, dubbed 1MDB, involving $4.5 billion of siphoned public funds.

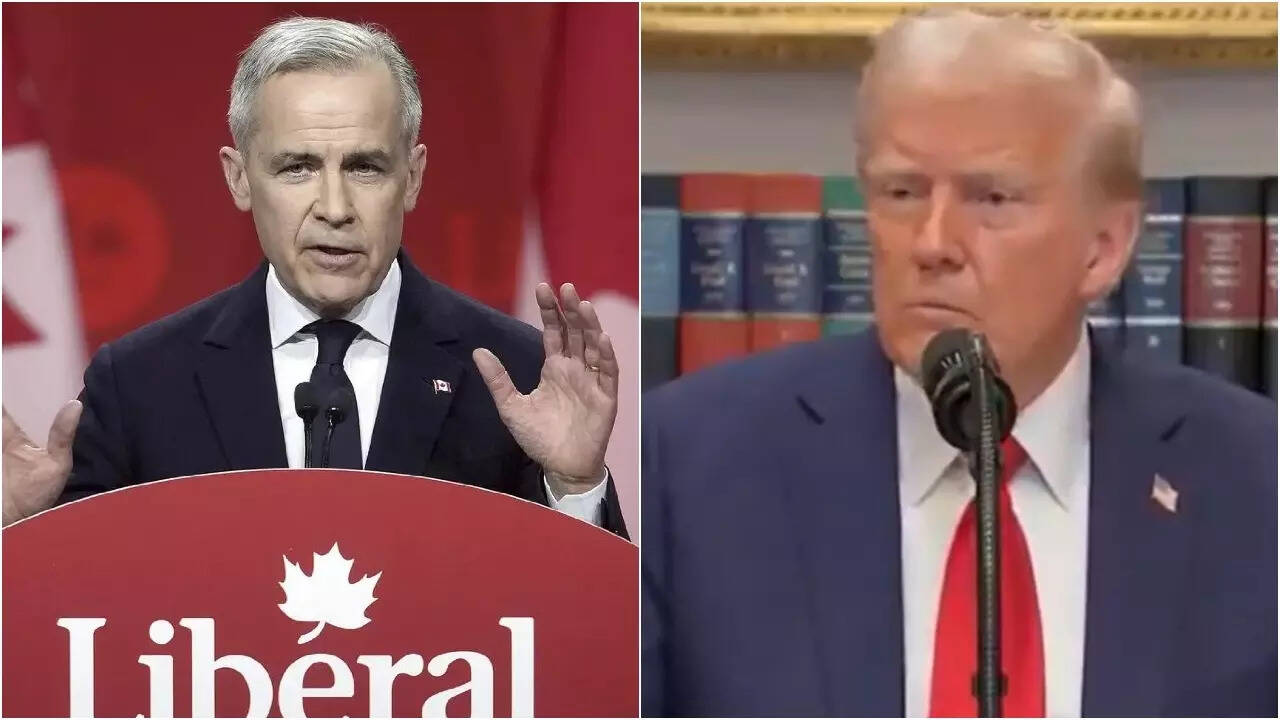

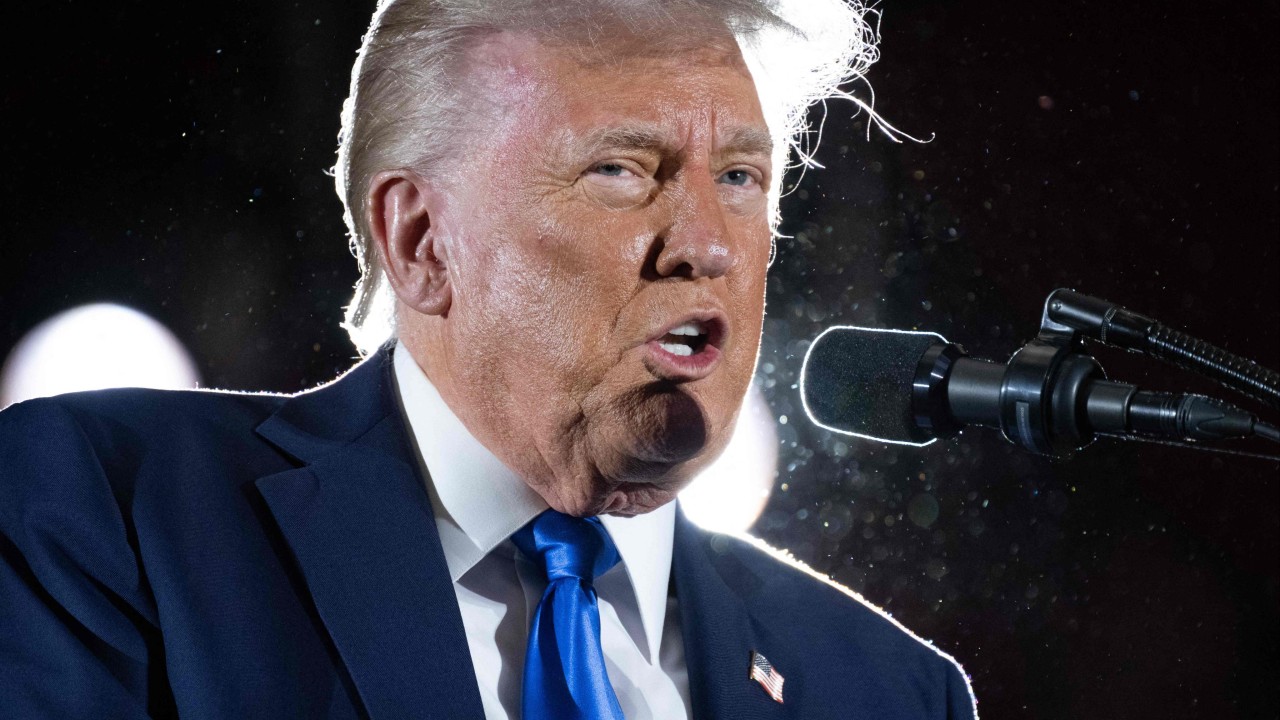

As Mahathir prepares for his 100th birthday in July, he gazes out at a world he spent a lifetime shaping but today struggles to recognize. In recent weeks, U.S. President Donald Trump has threatened to annex allies, bargained Ukrainian sovereignty with Russia behind Kyiv’s back, and launched an internecine trade war. Back in 2020, Mahathir warned that Trump’s return would bring “disaster.” Nothing in the intervening years has changed that opinion.

“Talking about taking over Greenland, Panama, and expelling people from Gaza—these kinds of things cannot be done now,” he says. “You have to consider the rights of people. This is not the way you run countries.”

To be clear, Mahathir was never much of a fan of more traditional American governments, eviscerating the Biden administration over its backing of Israel in the Gaza conflict and accusing NATO expansion of “provoking” Russia to invade Ukraine. But still the return of Trump has the nonagenarian exasperated—a sentiment that echoes around the developing world as tariffs and aid cuts threaten some of the globe’s most vulnerable.

“The U.S. used to talk about human rights, development, and things like that,” he says. “Of course, we thought that was great, because the U.S. itself was a British colony but became independent and a world power. So we wanted to learn from them. But now we are seeing a new U.S.”

Mahathir may have no overt policy role these days, but his views are far from an aberration. Still sprightly with a full head of silver hair, he is engaging and at times mischievous company. Today, he serves as he did throughout his life as a powerful advocate for the developing and Islamic world, where disgust with perceived American double standards has become a regular refrain in policy circles. “With regard to Ukraine, [Trump] said: Now you have to pay back; it is a loan. But with regard to Israel, it is not a loan,” he complains. “You are helping in committing genocide. And that is not a model we like.”

Still, Mahathir remains a complex and contradictory character: a champion of Malay identity while at times its fiercest critic; a denigrator of entrenched patronage networks who forged new ones in his own image; a strident critic of U.S. foreign policy under whom American investment boomed. To his supporters, Mahathir charted Malaysia’s remarkable economic development as Asia’s “fifth tiger” throughout the 1980s and ’90s. To his critics, his centralization of power and ruthless purge of opponents put Malaysia on an authoritarian trajectory.

In clawing back power from Malaysia’s nine royal families, Mahathir consolidated power in the position of Prime Minister as well as the president of UMNO, its oldest national political party. This dynamic was itself problematic but was compounded when the 1997 Asian financial crisis led to a string of Malaysia’s biggest companies being bailed out by the state, creating conditions ripe for rent-seeking behavior. Not that Mahathir agrees with the characterization.

They were “not bailouts,” he says. “When the collapse of a company will affect the economy, you need to stop that. The U.S. also did the same when your banks were collapsing. You have to take into consideration the fate of the workers and the subcontractors and all that.”

Mahathir also augmented affirmative action for Malaysia’s Malay majority so that it would better compete with its more industrious Indian and Chinese minorities, both of whom arrived in huge numbers during British colonial rule. While policies such as college places and public sector jobs for bumiputra—or “son of the soil”—candidates predate Mahathir, he went further to deliberately seed a Malay industrial class to keep means of production in their hands.

Yet for a figure who spent his career guarding against voracious Chinese entrepreneurship at home, Mahathir welcomed Chinese investment and is scathing of American efforts to contain the rising superpower. “They are very hard-working people, very skillful, you can’t stop them from growing,” says Mahathir. “China will do everything to retain the market and is doing exactly what the Europeans were doing before.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping recently wrapped up a state visit to Malaysia as part of a three-nation tour of Southeast Asia. In Kuala Lumpur, Xi and Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim unveiled 31 MoUs inked on subjects from AI to satellites. Other than hitting China with tariffs of up to 245%, the Trump Administration has adopted a hawkish posture toward Beijing, with Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth vowing during a visit to Asia earlier this month “robust, ready and credible deterrence in the Indo-Pacific, including across the Taiwan Strait.”

Yet the clear and growing danger is that perceived American hypocrisy regarding Ukraine and Gaza is now bleeding into discussions across the gamut of U.S. foreign policy, particularly over the future of self-ruling Taiwan. The fact that the U.S. officially adheres to a “One China Policy” regarding the island of 23 million—which officially broke from the mainland in 1949 at the culmination of China’s civil war and whose return Xi has called “the great trend of history”—yet still sells Taipei weaponry has been painted by Beijing as blatant interference in China’s domestic affairs. Today, at least 28 nations firmly support China’s push for “reunification.”

The truth is more complex: the U.S. “One China Policy” simply states that it “acknowledges” Beijing’s claim over the island without endorsing it. Taiwan’s population overwhelmingly favors maintaining its de facto independence. Still, Mahathir believes the U.S. is “provoking” Beijing toward a catastrophic conflict.

“China could have invaded Taiwan long ago but chose not to because Taiwan was useful,” he says. “But the U.S. is not happy because there is no confrontation. You send [former U.S. House Speaker Nancy] Pelosi there to do what? To provoke China. So now China wants to show its strength, and Taiwan now has to increase its defense capability, buying weapons from the U.S.”

Mahathir goes so far as to even call U.S. freedom of navigation sorties through the disputed South China Sea “destabilizing” and has called for them to withdraw. “Supposing China sends warships to the Caribbean and conducts [exercises] there, what would America do? This is not America, this is the South China Sea, this is Asia. The U.S. is a world power, but you have to use that power judiciously, not to provoke conflicts between nations.”

But what about China’s surprise live-fire naval drills off New Zealand in February, some 5,000 miles from China’s shores, which diverted dozens of commercial flights? Mahathir is unmoved, saying with a winsome grin: “New Zealand is still the Far East.”

It’s fair to say that of the undoubted qualities Mahathir possesses, introspection is not top of the list. His worldview has ossified, and there is perhaps understandably a sense that his country has left him behind. Asked whether he has any regrets, he immediately replies that he “antagonized my deputy, who is now the Prime Minister. And now he’s trying to seek revenge.”

It’s impossible to discuss Mahathir without bringing up Anwar Ibrahim, Malaysia’s current Prime Minister and Mahathir’s former protégé, who served as his deputy during the 1997 Asian financial crisis. But Anwar was sacked by Mahathir a year later and jailed on charges of corruption and sodomizing a male aide—accusations long decried by human-rights groups as politically motivated and that were eventually quashed in 2004, though Anwar’s return to the political fray was cynically curtailed by a second trumped-up sentence for sodomy in 2015.

After Anwar was purged, another Mahathir disciple, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, took over, but he eventually resigned under fierce criticism from Mahathir. Then came former Prime Minister Najib Razak, who today sits in jail following convictions of abuse of power and money laundering related to the 1MDB corruption scandal. “Najib thought that it doesn’t matter if people know he’s corrupt, because … with the money, he will remain as Prime Minister, nobody can touch him.” says Mahathir. “But it didn’t work.”

In order to oust Najib, Mahathir reconciled with Anwar, who was freed thanks to a royal pardon. The express understanding was that Mahathir would hand over power halfway through his term. “But before he could take over from me, the government collapsed, so I lost my position,” shrugs Mahathir. “I cannot give to him something that I myself no longer had.”

This retelling could be generously described as selective. The government collapsed in 2020 because Mahathir resigned in order to form a new party and stand for power again, sparking a political crisis as Anwar publicly declared he’d been “betrayed.” But the public had tired of Mahathir’s brazen shenanigans, and he was roundly defeated in a 2022 snap election, which returned Anwar’s party a plurality that allowed him to head a coalition government.

Today, Anwar and Mahathir are once again bitter rivals. Last March, Mahathir’s two eldest sons revealed that they had been ordered by Malaysia’s Anti-Corruption Commission into assisting with an investigation into their father. More than 10 top former allies of Mahathir have also been targeted by graft and tax evasion probes for alleged crimes going back decades. “The strategy of going after him indicates how Anwar has followed in Mahathir’s footsteps,” says Bridget Welsh, an honorary research associate with the University of Nottingham, Malaysia.

For Mahathir, Anwar is cut from the same cloth as Najib. “Anwar is a smart operator,” he says. “Obviously, you don’t see him taking money, but we know that lots of people are corrupt under his government.” (Anwar steadfastly denies he is targeting his former tormentor as well as graft allegations, telling TIME last August: “We are doing everything we can to combat corruption, no apologies about that.”)

Had Mahathir’s decades-long stramash with Anwar been an anomaly, it might have been attributed to a clash of ideals or personalities. Yet the fact that Mahathir has spectacularly fallen out with every single one of his successors does beg uncomfortable questions.

“What does this say about the system that Mahathir left behind him?” asks Francis Hutchinson, coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Program at the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore. “If you don’t think you have worthy successors, should you not have a system with more checks and balances?”

If Mahathir’s initial legacy for Malaysia is a more autocratic political system, then his second stint as Prime Minister was framed as a popular crusade to restore democracy. No shortage of leaders have moved in the opposite direction—not least the current occupant in the Kremlin, under whom Russia has transitioned from flawed democracy to unfettered dictatorship.

Mahathir recalls meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2005. It was two years after Mahathir had stepped down as Prime Minister, though in a sign of his enduring authority, Putin visited him at home. “Actually, I told him, ‘You cannot come to my house; protocol-wise it’s wrong,’” recalls Mahathir. “But he insisted.”

Upon arrival, Putin’s entourage were aghast to learn that Mahathir’s house didn’t even have a perimeter wall. “For [Putin’s] security, to have somebody like me with no fence was unthinkable,” laughs Mahathir. “But we had a four-hour meeting. He was interested in seeing how Malaysia managed from an agro-based country to become industrialized. He was going to rebuild Russia. When I talked to him it was about development, increasing trade, basically to be less communistic, to make use of capitalist ideology.”

So to what does Mahathir attribute the return of war in mainland Europe that has so far resulted in millions displaced, 172,000 killed, and 611,000 wounded and counting? Again, it’s a matter of the West “provoking” Russia, he says. Mahathir argues that NATO should have been abolished after the Moscow-led Warsaw Pact counter bloc was dissolved following the fall of the Soviet Union. “Instead, NATO decided to take all the Warsaw Pact countries and join NATO and confront Russia,” he says. “Before Ukraine can join NATO, Russia took preemptive action.”

In no legal context is “provocation” a complete justification that absolves guilt, though Mahathir is determined to heap responsibility on Western powers. “I get this feeling that Europe likes to have enemies,” says Mahathir. “If it’s not Russia, it’s the Islamic countries.”

At a recent meeting in Vladivostok, Anwar praised Putin for “vision and leadership,” prompting rebukes in Western diplomatic circles. But engaging with Putin is one decision that Mahathir declines to criticize Anwar for. “I think we had to sit down with Putin,” he says. “I would have sat down with him.”

Is it not positive then to see Trump willing to engage with Russia? “We don’t see Presidents of the U.S. taking that kind of stand, actually agreeing with the Russians and all that,” admits Mahathir with a weary sigh.

“I don’t think he understands the world,” Mahathir says of Trump. “He’s 100 years behind the times.” Says one of the few men qualified to know.

What's Your Reaction?