There’s a Better Way for Trump to Boost the Birth Rate

Embrace all the people who already want kids, but struggle to have them.

American households don’t look like they used to. They’ve been changing for decades, in part because fewer people have been having kids—but also because different people have been having kids. More unmarried couples have been starting families. More single people have been parenting on their own. Some are even raising children with their friends. According to a report from Pew Research Center, in 1970, 67 percent of Americans aged 25 to 49 lived with a spouse and at least one child; by 2023, that number had plummeted to 37 percent. That’s a profound shift: Most adults in this age group, over the course of roughly 50 years, went from being married with children to not. What some refer to as the “traditional” family is no longer a majority.

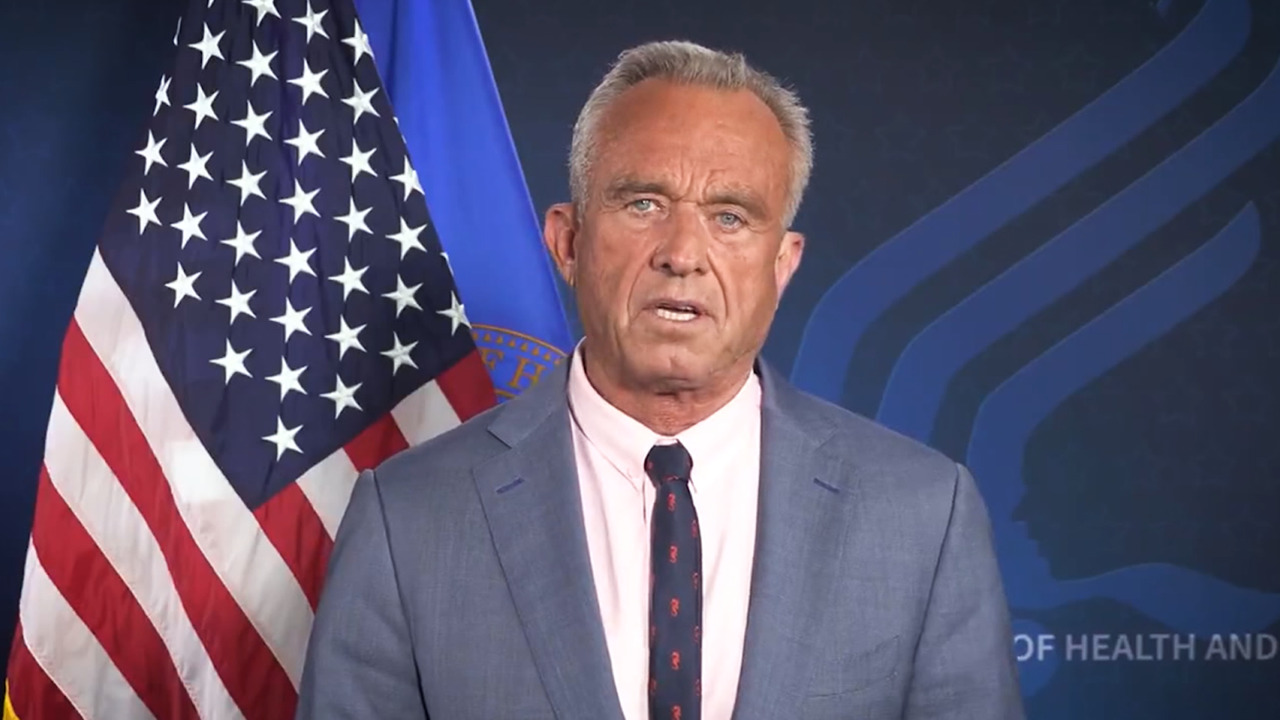

Pronatalists across the political spectrum argue that the first trend, dropping birth rates, poses an urgent, existential threat: Fewer children born could eventually mean fewer working people to support the economy, pay taxes, and care for the elderly. Some of these pronatalists have the ear of Donald Trump, who, according to The New York Times, is weighing policies intended to nudge people toward childbirth. Vice President J. D. Vance and DOGE chief Elon Musk are both enthusiastic pronatalists. But the administration also wants to promote marriage—most likely a certain kind of marriage. Project 2025, a set of policy suggestions that have been called a road map for Trump’s second term, is very clear about who should be encouraged to have children. “Married men and women,” it decrees, “are the ideal, natural family structure.”

A pronatalist policy that defines family so narrowly—acknowledging only a type of household that most Americans don’t fit into—wouldn’t just be a moral mistake; it would also be a strategic one. The United States is full of people yearning for children, but who are struggling to find a partner, or to pay for IVF, or to afford caring for kids beyond those they already have.

Not everyone agrees that more babies are necessary to sustain a society: Some argue that governments can find other ways to invest in the economy, fund social services, and support older adults. But if raising fertility rates is the goal, Trump’s team should be embracing the many kinds of families that already exist—and lowering barriers for all the people hoping to start new ones.

Not every pronatalist is the same. Some advocate for using technology—AI-assisted in vitro fertilization, genetic engineering, artificial wombs—to “optimize” humanity and stave off what they see as a potentially apocalyptic demographic collapse. (If the birth rate doesn’t spike soon, Musk has said, “civilization will disappear.”) Others make a progressive case for pronatalism: spurring childbirth by prioritizing aid to working families, thus smoothing the way for women to have as many kids as they’d like. (If such a model “helps women manifest the lives they imagine for themselves,” Elizabeth Bruenig recently wrote in The Atlantic, it’s “arguably feminist.”) Many pronatalists want a return to bygone family norms: stay-at-home moms having lots of kids. The Heritage Foundation, the conservative think tank behind Project 2025, which advocates for “familial, in-home childcare,” fits into this bucket.

The White House may not follow Project 2025’s family plan to a T. The policies it’s considered so far, according to the Times, run the gamut from sensible if insufficient (a $5,000 “baby bonus” for every new American mother) to somewhat strange (a plan to help women understand when they’re ovulating—as if low fertility rates are caused largely by people who are trying to conceive but just haven’t figured this out).

[Read: Grandparents are reaching their limit]

Still, the administration hasn’t exactly been shy about how it defines family. “I want more happy children in our country, and I want beautiful young men and women who are eager to welcome them into the world,” Vance declared at this year’s March for Life anti-abortion rally. And the White House evidently wants its straight couples betrothed. Research shows, though, that efforts to boost marriage or birth rates don’t actually need to be lumped together—though research generally shows that children fare better across several metrics when raised in two-parent households.

Typically, marriage-incentive programs encourage unmarried couples to wed based on the idea that marriage will make them more likely to pool incomes, create stability, and raise kids in a two-parent household—a setup generally associated with better educational and workforce outcomes for children. But marriage itself hardly guarantees those successes, Christina Cross, a Harvard University sociologist and the author of the forthcoming book Inherited Inequality, told me.

Families often benefit from two parents working as a team; it’s just not a magical fix-all. The people most likely to marry are affluent, educated, white or Asian, and straight. Cross’s research indicates that what’s influential for kids is not just the resources that tend to accompany marriage, but also the resources that people who end up marrying already tend to possess. When Cross studied Black, low-income families, she found that even when children were raised in two-parent homes, they did not end up with the same resources, educational achievements, or prospects in the labor market as children from more affluent families. The benefits of the two-parent structure, she said, “are just not universal.” And of course, anyone raised by two miserably married, constantly arguing parents might tell you the same thing.

[Read: The slow, quiet demise of American romance]

At least half a century of research supports the idea that a household arrangement itself isn’t what makes a kid happy and healthy. Susan Golombok, a University of Cambridge psychologist and the author of We Are Family: The Modern Transformation of Parents and Children, has for decades studied nontraditional families: gay couples who adopt, gay couples who rely on IVF and surrogacy, single parents by choice. Again and again, she and other researchers have found that what counts more for kids is two things: the quality of their relationships with family members, and whether they’re accepted by the outside world. Golombok has even found that parents in nonconventional family structures tend to be more involved than straight, married parents on average, probably because they are more likely to have deliberately chosen parenthood. Gay couples and single parents by choice have to be intentional, to overcome obstacles. “These were really wanted children,” she told me. Now she’s seeing many politicians and commentators blatantly ignore such findings. “All of this very painstaking research,” she said, “is just being brushed to the side as if it didn’t happen.” And erasing it isn’t likely to lead to a baby boom.

Consider, for instance, how many people want kids but don’t have anyone to raise them with. The United States is already in the midst of a romance recession: Fewer Americans, and especially people without college degrees, are marrying or living with partners; more people are identifying as single. Badgering people to hurry up and get hitched isn’t likely to change this. Straight women, in particular, are trying to pull from a pool of men who—with their growing rates of addiction, isolation, unemployment, and even suicide—may not seem stable or healthy enough for parenthood. As these women search and search for a partner, their window for having children might close. For her 2023 book, Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs, Marcia C. Inhorn, a medical anthropologist at Yale, interviewed 150 women who’d frozen their eggs; more than 80 percent of those participants, it turned out, were single. They were putting up with a hugely expensive and uncomfortable process just to buy themselves a little more time to find a co-parent. Some never did.

The White House has plenty of options to make having and raising a kid alone more feasible. It could start by subsidizing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) such as in vitro fertilization, which Trump has said he might do—or then again, maybe he won’t. In March, he called himself “the fertilization president,” and his aides are reportedly planning to recommend ways to make IVF more accessible. But his administration has also been cutting federal programs that research fertility and maternal health, including one that tracked the success rates of different IVF clinics. And Project 2025 explicitly states that ART should be a last resort even for married couples—instead recommending “restorative reproductive medicine,” a vague term for methods such as fertility tracking that are far less likely to work for people striving to conceive.

[Read: This might be a turning point for child-free voters]

Policy makers could also think beyond conception, accounting for the loved ones whom single people (and parents in general) may turn to for help when they need it. Cross, the sociologist, mentioned that a lot of families—especially low-income, Black, and Latino families—depend on extended relatives to help raise kids. That lines up with my recent reporting on grandparents, many of whom are pushing themselves to their limits providing child care. (Researchers told me that reliance on grandparents has likely increased along with the rise in single parents.) Given these realities, family-leave policies should arguably extend not only to spouses and their children, as many are limited to now, but to anyone responsible for taking care of a family member. The U.S. could even follow Sweden’s example and let parents transfer paid-leave time to grandparents in the first months after their kid’s birth.

Or what if the government, acknowledging all those partnerless adults, were to encourage Americans to raise kids with friends? Some people are already doing it. Golombok has been studying platonic co-parents in recent years, and so far, she told me, the data suggest that their children are just fine. And if pooling incomes is good for kids—well, a group of pals combining finances, skills, and sets of hands might be even better.

The Trump administration hasn’t shared the details of its pronatalist agenda; it could take some of the recommendations reported in the Times, or go another way entirely. Offering that “baby bonus” would be a good start. Subsidized child care, guaranteed paid parental leave and sick leave, tax credits or cash assistance totaling more than a few thousand dollars would be even better. Such policies, as long as they’re not limited to straight, married couples, would help a wide range of households—including traditional ones.

But if the Trump administration doesn’t institute policies that help the actual majority of American families, it won’t be advancing a family-forward agenda at all. And it won’t be likely to create “more happy children.” Its goal has always been regression: not to open up the circle of parenthood, but to shut it.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic

What's Your Reaction?