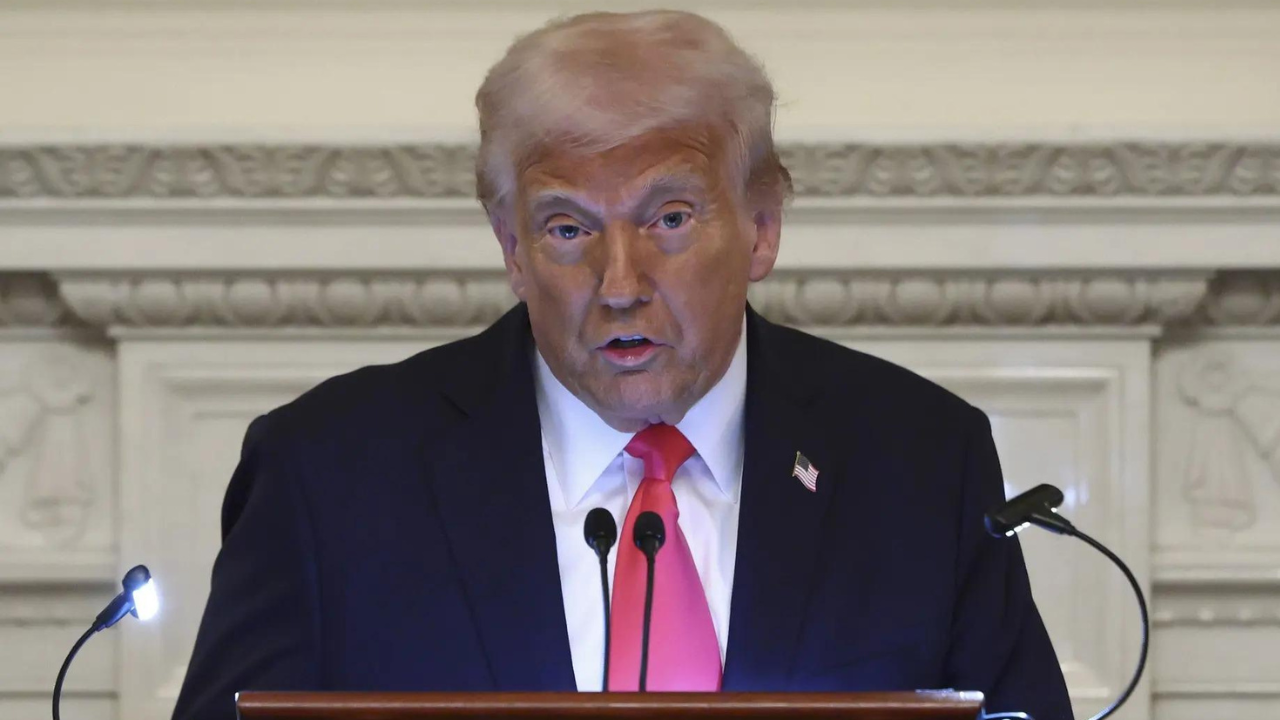

What Trump Learned From the First Travel Ban

The administration has found a legal strategy to help it obfuscate significant factual details: go fast.

The litigation over the government’s summary renditions of foreign nationals to an El Salvador prison, with no due process of law, is now at the Supreme Court’s door. The justices will soon decide whether to relieve the Trump administration from the trial court’s order halting the expulsions. Whether the government has complied with the order isn’t directly before the Supreme Court. But whether the Court can trust the government’s representations during such quickly unfolding litigation is—and the justices have every reason not to.

In this and other cases now being litigated, the government is following a playbook established during the fight over the first Trump administration’s travel ban, which barred entry into the United States from several majority-Muslim countries. From that litigation, the administration learned a strategy for implementing portions of its legally dubious agenda without the Court’s explicit blessing: go fast. Speed facilitates obfuscation. By pushing litigation to a breakneck pace—and changing the underlying details just as quickly—the administration was able to get the Supreme Court’s approval for policies without full legal scrutiny. That same approach is once again under way in the deportations case and in others now before the Court.

The story of the first Trump administration’s travel ban began on Friday, January 27, 2017, when the administration announced a prohibition on travel from seven majority-Muslim countries with no exceptions, including for people with ties to the United States, such as green-card or visa holders. It did so with no advance warning, which meant passengers boarded flights not knowing they wouldn’t be allowed to enter the United States. The policy was sloppy, cruel, and riddled with animus—so blatantly illegal that the Trump administration declined to continue defending it after lower courts invalidated it.

[Tom Nichols: Trump’s authoritarian playbook]

With the slapdash version dead, the administration came up with a (slightly) modified policy that appeared more legitimate, at least on a superficial level. The second ban, unlike the first, did not apply to visa and green-card holders. This one was also purportedly temporary: As written, it was set to last for 90 days, during which time the administration said it would conduct a formal review to determine what kind of permanent travel restrictions were warranted. Despite these nominal changes, it still reeked of illegal animus.

The administration asked the Supreme Court for permission to implement the temporary ban, but it did so in a strategic way that would enable the Court to give its okay without having to decide the substantive question of whether the measure was legal. Here’s how that worked: In spring 2017, the U.S. Courts of Appeal for the Fourth and Ninth Circuits blocked the new ban. The government then turned to the Supreme Court, requesting emergency relief from those decisions. Curiously, the government requested expedited briefing (a rush on the papers both sides file in a case), but not expedited oral argument. In fact, it asked the Court to delay hearing the case until the fall, at which point the policy would have expired. By making its request in this way, the government was asking for an up-or-down vote on the lower court’s decision, but not a full consideration of the legal merits.

This gambit paid off. The Court allowed the administration to partially enforce the second travel ban for 90 days. By the end of that period, the administration had rolled out the third and final iteration—so that the third ban went into effect just as the second expired. The Court heard oral argument over whether the third iteration of the policy was invalid in spring 2018, and a few months later, the Court upheld it. In effect, the second version bought the administration time to put together a policy that looked more legitimate while it enforced a less legitimate version. The administration could claim that the third ban emerged from a formal process and had undergone significant revisions, rather than being fired off on a whim and on the basis of animus. But in the meantime, the administration was able to do what it wanted anyway: suspend entry from several majority-Muslim countries into the United States. And that may have made the Court more comfortable with accepting the third version, because a ban was by that point the status quo.

Part of the reason this worked is that the administration managed to get the Court to act quickly, without a careful parsing of the facts. That was a smart move, because actually defending the policy on a factual basis would have been quite a challenge. During the oral arguments over the third ban, the justices asked the Trump administration’s lawyer, Solicitor General Noel Francisco, about the waiver process—the mechanism that might allow people to show, on an individual basis, that they should be allowed to enter the United States. The solicitor general assured the Court that the process was available to people via consular officers. But after the argument, consular officials said that they had no authority or discretion to grant waivers, and that only certain officials in Washington could do so. The problem was that by then, the ban was in effect.

The new Trump administration now appears to be deploying a similar strategy in much of the litigation over its policies. For example, the recent litigation over the attempted shutdown and defunding of USAID confirmed that the administration is still trying to couple speed with factual opacity.

[Read: The cruel attack on USAID]

In that litigation, the administration claimed to possess the outlandish authority to cancel spending items that Congress had appropriated and approved—not just for USAID, but for other agencies, grants, and contracts. Numerous federal district judges have found several of the administration’s funding freezes unlawful. The relevant federal law, the Administrative Procedure Act, allows courts to block certain agency actions. That’s just what the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia did in the AIDS Vaccine Advocacy Coalition v. United States case—block the administration’s implementation of an across-the-board funding freeze at USAID.

The administration rushed to the Supreme Court to free itself from lower-court decisions blocking its initial version of the policies. In particular, the administration requested relief via the Supreme Court’s “shadow docket.” Again, this is right from the travel-ban playbook.

The administration’s lawyers asked the Court to act quickly while insisting that it wasn’t possible to pay out the contracts that had been subject to the initial USAID freeze, which the district court had effectively ordered it to honor. And because the case was developing so rapidly, the government’s timeline did not give the justices much chance to familiarize themselves with the details. As with the travel ban, a rushed job stood to benefit the administration by increasing the odds that the Court would take the government at its word without really looking into things deeply.

In this instance, the administration did not prevail, but it certainly tried. Before the Supreme Court, the government said that it was “not logistically or technically feasible” for it to pay the 2,000 or so invoices ordered by the district court. The justices refused to pause the district court’s ruling, instead allowing the court to determine whether a preliminary injunction was warranted, and directing it to act with “with due regard for the feasibility of any compliance timelines.” Left with time to develop and consider more facts, the district court pointed to a declaration by Peter Marocco, the acting director for USAID, acknowledging that prior to January 20, 2025, both USAID and the State Department could process several thousand payments a day. This temporary victory for the rule of law might not last, however; the litigation may yet head back to the Supreme Court, where the administration’s rush strategy could eventually win out.

If the Court accepts what the government is saying now in the summary-expulsion case, it will be risking its own credibility. In that case, the administration is asking the Court to credit, without evidence, several of its assertions. Among them is the unbelievable claim that individuals facing summary expulsion would somehow be able to challenge their prospective expulsion even though they may not know they are about to be sent to a foreign prison.

The Court should reject the government’s request to pause the lower court’s decision and recognize that its rush strategy is designed to make a mockery of the rule of law, not to mention the concept of facts. As they say, fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice …

What's Your Reaction?