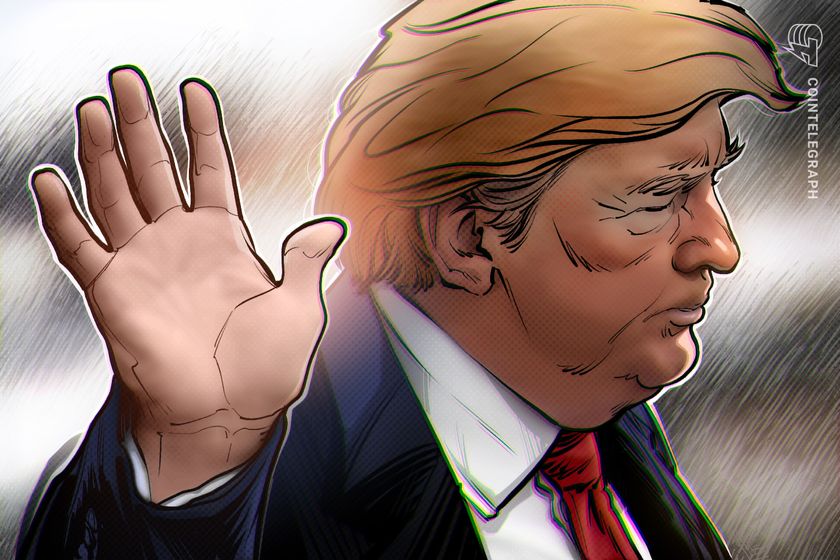

Why Trump Will Blink First on China

A trade war is injurious to both sides but Beijing is more confident that time is on its side.

U.S. President Donald Trump will probably blink first. The first sign of that came Tuesday when he said that 145% tariffs on China will “come down substantially” and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent predicted “de-escalation” in the de facto trade embargo between the world’s two largest economies.

Both sides would certainly benefit from finding agreement. The trade war has vaporized trillions of dollars from the stock market, caused the dollar to plunge, and tipped America’s economy closer to recession. Chinese freight ship bookings have also plummeted in recent weeks, suggesting downward pressure on China’s export sector, an engine of the country’s economic growth. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Yet there are still major obstacles to striking a deal. There is no serious U.S.-China negotiating process underway, and therefore no off-ramp on the immediate horizon. And that is, in part, because Beijing is not in the mood to build one.

Read More: Why China Can’t Win a Trade War

China’s leaders believe their political system is more unified, hardened, and disciplined than the Trump Administration to withstand a trade war. They do not face competitive elections or political blowback from market movements like in the U.S. They also have considerable leeway to shape the public narrative about the trade war through state-controlled media.

Moreover, China has tools at hand to hit America’s economy where it hurts, including the withholding of critical minerals and key inputs to America’s industrial value chains. A prolonged trade war could shudder U.S. factories, cause job losses, and lead to higher inflation and empty store shelves. China’s leaders seem to expect America’s political feedback loop will kick in quicker and sharper for Trump than for Xi Jinping. In other words, Beijing believes time is on its side.

That is why China will be cautious about entering into trade negotiations. Since its leaders believe they have leverage and can afford patience, they will not negotiate against themselves. They will wait for Trump to define what is up for negotiation.

Trump has insisted that “the ball is in China’s court” and that it must “ultimately” make a deal to preserve its access to the U.S. market. The problem for Trump, though, is that virtually nobody in Beijing agrees with this assessment. In Trump, China’s leaders see an improvisational leader who frequently changes his mind and rarely sticks to agreements for long.

Given these dynamics, fairly or not, if there is going to be a climb down on the trade war, it will need to come from Trump. It is not going to originate in Beijing.

To get to a deal, Trump will need to identify his objectives and then empower his staff to negotiate on his behalf. He will also need to read the room. Beijing craves respect. It will only agree to a deal that it can present at home and abroad as a win for itself, too.

During his first term, Trump signed a U.S.-China “Phase One” trade deal. As part of the deal, Beijing committed to purchase at least $200 billion in additional U.S. goods and services above 2017 levels. The deal ultimately underperformed; Beijing did not follow through on its purchasing pledges. As such, there will not be U.S. appetite for a do-over of negotiating commitments for future purchases of American goods and services.

The challenge, then, is to find an overlap of interests between Washington and Beijing that could allow both sides to justify negotiations. There are a few potential building blocks for such a deal. For example, Beijing has publicly signaled its intent to boost domestic demand. A tangible and time-bounded effort to deliver on that could be mutually beneficial. Greater domestic demand would spur Chinese growth while reducing export flows to U.S. and global markets.

Trump might also be open to negotiating around Chinese investment into the American heartland to boost manufacturing capacity in non-national security sectors. Chinese investments there would allow Trump to claim progress in American re-industrialization, while Xi could tout success in expanding scope for homegrown firms to make profits in the U.S. market.

Given the hardening politics in both countries around the trade war, even this modest set of outcomes might seem out of reach. But the alternative would be to let the trade war rumble, and the diplomatic calendar to run its course.

Both Trump and Xi will likely attend the APEC leader’s meeting this November in South Korea. That will be the first time and place where they can be expected to be together. A meeting could allow both leaders to set a course for negotiators to follow.

The possibility of talks before November is still there. A small exit door remains available for both sides to escape the mounting costs of the trade war. Xi is not going to open that door, though. If anyone is going to kick the door open, it will need to be Trump.

What's Your Reaction?