The Dark Weirdness of R. Crumb

The illustrator dredged the depths of his own subconscious—and tapped into something collectively screwy in America.

Certain great artists are synonymous with their kinks. Egon Schiele had his thing for gaunt girls and their undergarments. Robert Mapplethorpe was partial to bulging muscles wrapped in leather. And then there is the legendary cartoonist R. Crumb—lover of solid legs, worshipper of meaty thighs, champion of the ample backside. To truly know his art is to know what turns him on.

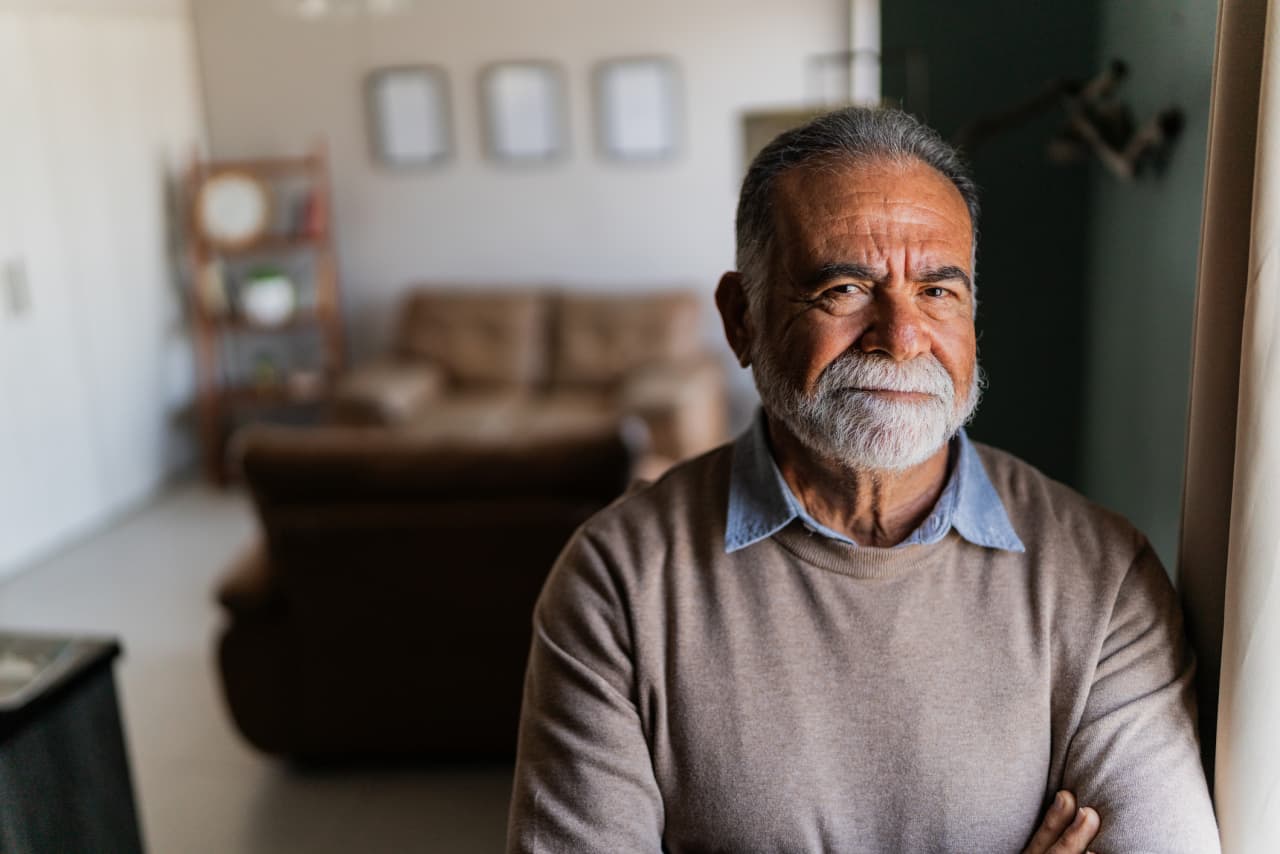

For the man who effectively invented underground comics in the 1960s, rubbing his readers’ faces in his sexual proclivities was always the point. If Crumb, now 81, was helpless against his own desires—and there he was on the page, quivering and sweating behind his thick glasses as he beheld one of his zaftig goddesses—he suspected that, somehow, everyone else was also helpless against theirs. His comix, as he renamed them, epitomized the hippie turn of the decade because he dove to the depths not just of his own subconscious, but of something collectively screwy, bringing up all the American muck.

He was the anti–Norman Rockwell the culture was craving. But this was also the gamble of his art. Diving down like that, he risked derision—being called a sicko, a misogynist, a racist (all labels he indeed could not escape).

In a loving biography, Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, Dan Nadel begins with a childhood memory that Crumb preserved in a 2002 comic, “Don’t Tempt Fate.” A slouchy young Crumb is standing in a junkyard next to a boy who is hurling pieces of cement over a cinder-block wall. Crumb is appalled by the “total obliviousness” of the boy, who doesn’t care that he might really hurt someone. To demonstrate the danger, Crumb then does “the crazy thing” and walks to the other side of the wall, where a chunk immediately hits him in the mouth, knocking out a front tooth with a perfect comic-book “BAM!” The crux of Crumb, Nadel writes, can be found in this anecdote, where “the compulsions of masochism, sadism, and martyrdom are conjoined.”

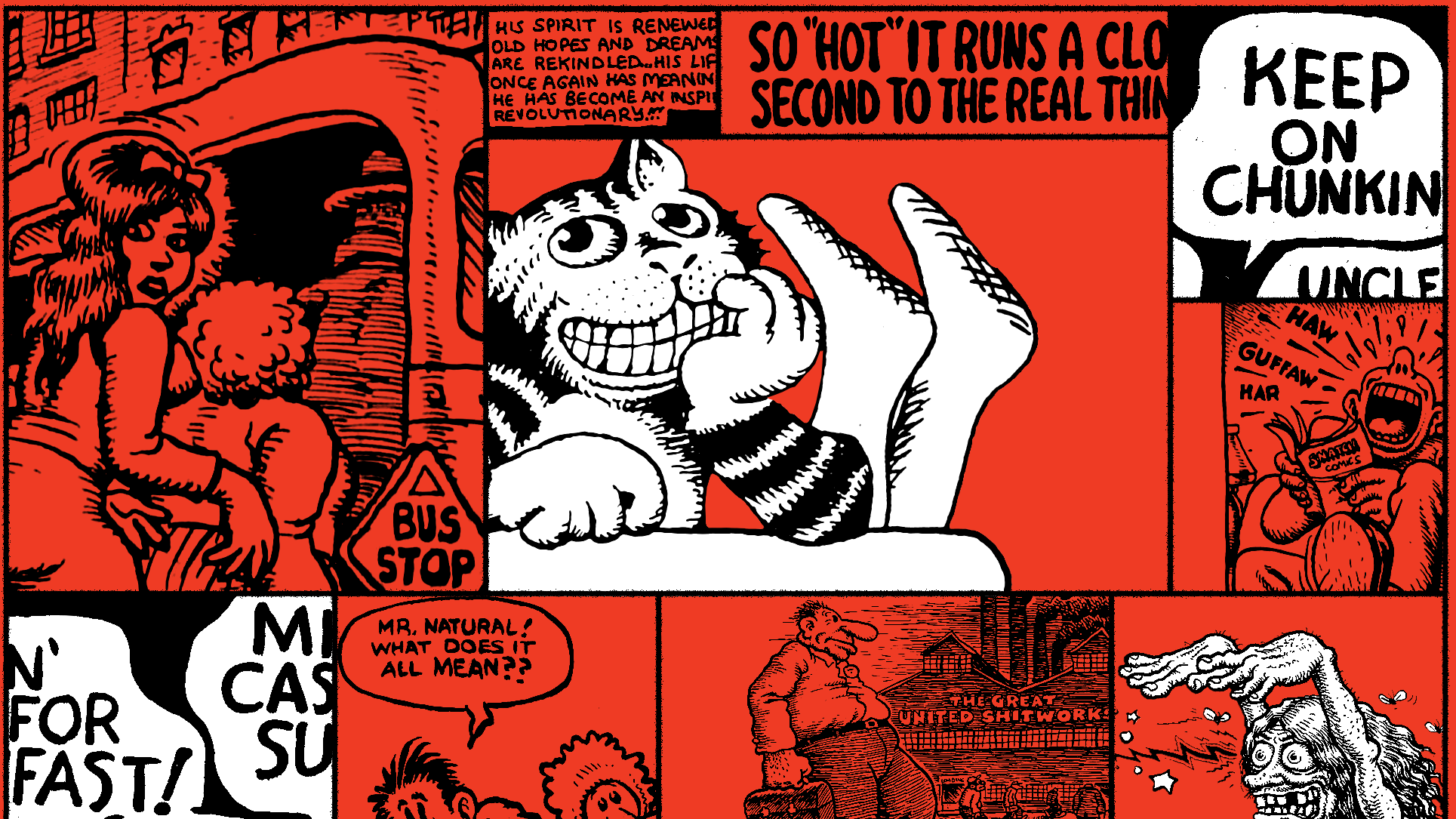

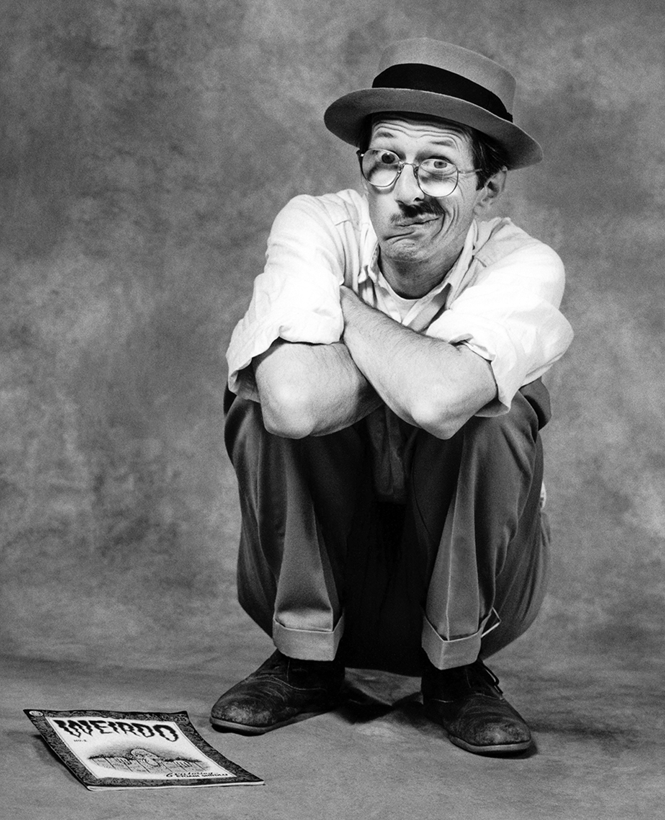

Crumb’s gawky, eccentric persona was first revealed to the wider public in a 1994 documentary made by his friend Terry Zwigoff, which portrays the cartoonist with all of his incongruities. On the one hand, he’s a man who seems of another era: dressing in a fedora and suit jacket, obsessively collecting blues and country records from the 1920s and ’30s, and using a crow-quill pen to draw in a meticulous crosshatch style reminiscent of Thomas Nast’s 19th-century political cartoons. On the other hand, he’s flagrantly free of inhibition; unabashed in his sex-craziness; creating preposterous characters, such as an urbane, horny cat named Fritz and a pleasure-loving pseudo-guru with a long beard, Mr. Natural. Crumb is both a recluse in need of frequent monk-like retreats from the world and a man with a fetish for requesting piggyback rides from women he has just met.

If the documentary presented him as a sort of accidental artist, with little other than his id propelling him from drawing to drawing, a more intentional drive emerges in the biography. Crumb found his audience in the late ’60s after he arrived in San Francisco, escaping the violence and mental illness of his dysfunctional Philadelphia family and the dead-end job drawing greeting cards in Cleveland that followed.

With LSD fueling his visions, he began drawing bizarre, big-footed figures in absurd comics, many of them disjointed, grotesque, as if Samuel Beckett were expressing himself with a Sharpie on the wall of a bathroom stall. Here’s Nadel on one of Crumb’s first breakout strips, “Har Har Page,” from 1966:

It begins with a rotund male wiping snot on a nude woman, then chasing her with a bus, which multiplies to infinite buses. He attempts to assault the woman, who in turn throws a toilet at him; he finally manages to capture her, only to be swept away by a janitor. Reappearing, the man drags the woman and eats her foot.

Crumb desecrated sleek American surfaces in a way that felt disturbing and profound, especially to the many young people also dropping acid. The title of another strip from this era neatly captured his critique of a society that he felt still needed to shake off its ’50s conformity: “Life Among the Constipated.” By 1969, he had drawn the cover for the album Cheap Thrills, at the request of the band’s lead singer, Janis Joplin; started one of the first underground comic books, Zap Comix; and signed a deal with a major publisher for a collection of his strips.

Though Crumb and his many fans have always called his creations sharp social satire, he made art out of the kinds of insecurities and brutal fantasies that today might claim a niche porn category or live on a subreddit for incels. In his 1969 strip “Joe Blow,” a standard-issue 1950s nuclear family joyfully descends into depraved acts of incest, father and daughter, mother and son. In an early-’90s strip, “A Bitchin’ Bod,” Crumb presents a woman, “Devil Girl,” whose body has all of his favorite features, but no head—available for sex and incapable of speech or thought. Is Crumb here revealing the culture’s violent misogyny, or his own? It’s honestly hard to tell.

In a 1994 issue of his comic book Weirdo, Crumb drew a pair of visions that were meant to illustrate the fears that he imagined lived within white Americans: “When the Niggers Take Over America!,” which featured Black men killing white men and raping white women, and “When the Goddamn Jews Take Over America!” in which shady cabals use psychoanalysis to subvert the Christian population. Even Art Spiegelman, the most famous of Crumb’s subversive-cartoonist progeny, admitted that it didn’t really work as satire, and a white-power newsletter soon reprinted a bootlegged copy of both in its pages, very much proving Spiegelman’s point.

Crumb became aware early in his career of a dynamic that any online shitposter today is all too familiar with: The darker he got, as he noted in a long entry in one of his 1975 sketchbooks, the more positive reinforcement he received. The moment was right for an artist so willing to reveal his “own subconscious yearnings,” as he put it. But a spiral followed: “Then when they love you for it, make a hero out of you and interview you to death, you (me) over-react and start drawing socially irresponsible and hostile work which you (I) then feel guilty about.”

Crumb mellowed his approach over the decades, perhaps having stretched nearly to its breaking point the kinetic power of comics to illustrate transgressive thought, emotion, and fantasy. His work grew more introspective and psychological. In a less constipated America, he was free to explore his own neuroses. And he took on subjects for the sheer technical challenge. Who would have predicted 40 years earlier that his last great work, published in 2009, would be a faithful illustration of the entire Book of Genesis, the decadent Mr. Natural replaced by the moral force of the Old Testament God?

Aline Kominsky-Crumb, his partner of half a century and a comics artist in her own right who died in 2022, was also clearly a stabilizing force. Robert and Aline often drew together and had the rare open marriage that seemed to have been relatively serene—they knew that they needed each other, and that being a couple was never going to be enough. They also knew that they needed escape, much as they both appreciated provocation. They ended up in Sauve, a village in the south of France, where Crumb still lives, surrounded by his daughter, Sophie, and three grandchildren.

Despite his stature now as a founding father of the graphic novel, there is a strong case for placing Crumb’s signature work in the groaning file labeled “problematic.” We live in a moment awash in just the sort of winking sarcasm that could be read as genuine hate or a joke or both—the Pepe the Frog meme that’s maybe racist, the wave that’s maybe a Hitler salute. But what saves Crumb is the shakiness of his hand—in being creepy or dark or dangerous, he was also making himself terribly vulnerable, and he knew it.

*Lead image sources: Graeme Robertson / Getty; Dave Randolph / San Francisco Chronicle / Getty; Aurica Finance Company / Black Ink / Fritz Productions / STE / RGR Collection / Alamy; Chris Jackson / Getty; United Archives GmbH / Alamy.

This article appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “The Anti-Rockwell.”

What's Your Reaction?