The Rise of the Vineyard Vines Nihilists

MAGA populists claim to be helping the working class, but they’re really after one thing: raw power.

Illustrations by Ricardo Tomás

Charles de Gaulle began his war memoirs with this sentence: “All my life I have had a certain idea about France.” Well, all my life I have had a certain idea about America. I have thought of America as a deeply flawed nation that is nonetheless a force for tremendous good in the world. From Abraham Lincoln to Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan and beyond, Americans fought for freedom and human dignity and against tyranny; we promoted democracy, funded the Marshall Plan, and saved millions of people across Africa from HIV and AIDS. When we caused harm—Vietnam, Iraq—it was because of our overconfidence and naivete, not evil intentions.

Until January 20, 2025, I didn’t realize how much of my very identity was built on this faith in my country’s goodness—on the idea that we Americans are partners in a grand and heroic enterprise, that our daily lives are ennobled by service to that cause. Since January 20, as I have watched America behave vilely—toward our friends in Canada and Mexico, toward our friends in Europe, toward the heroes in Ukraine and President Volodymyr Zelensky in the Oval Office—I’ve had trouble describing the anguish I’ve experienced. Grief? Shock? Like I’m living through some sort of hallucination? Maybe the best description for what I’m feeling is moral shame: To watch the loss of your nation’s honor is embarrassing and painful.

George Orwell is a useful guide to what we’re witnessing. He understood that it is possible for people to seek power without having any vision of the good. “The Party seeks power entirely for its own sake,” an apparatchik says in 1984. “We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power. Not wealth or luxury or long life or happiness: only power, pure power.” How is power demonstrated? By making others suffer. Orwell’s character continues: “Obedience is not enough. Unless he is suffering, how can you be sure that he is obeying your will and not his own? Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation.”

Russell Vought, Donald Trump’s budget director, sounds like he walked straight out of 1984. “When they wake up in the morning, we want them to not want to go to work, because they are increasingly viewed as the villains,” he said of federal workers, speaking at an event in 2023. “We want to put them in trauma.”

Since coming back to the White House, Trump has caused suffering among Ukrainians, suffering among immigrants who have lived here for decades, suffering among some of the best people I know. Many of my friends in Washington are evangelical Christians who found their vocation in public service—fighting sex trafficking, serving the world’s poor, protecting America from foreign threats, doing biomedical research to cure disease. They are trying to live lives consistent with the gospel of mercy and love. Trump has devastated their work. He isn’t just declaring war on “wokeness”; he’s declaring war on Christian service—on any kind of service, really.

If there is an underlying philosophy driving Trump, it is this: Morality is for suckers. The strong do what they want and the weak suffer what they must. This is the logic of bullies everywhere. And if there is a consistent strategy, it is this: Day after day, the administration works to create a world where ruthless people can thrive. That means destroying any institution or arrangement that might check the strongman’s power. The rule of law, domestic or international, restrains power, so it must be eviscerated. Inspectors general, judge advocate general officers, oversight mechanisms, and watchdog agencies are a potential restraint on power, so they must be fired or neutered. The truth itself is a restraint on power, so it must be abandoned. Lying becomes the language of the state.

Trump’s first term was a precondition for his second. His first term gradually eroded norms and acclimatized America to a new sort of regime. This laid the groundwork for his second term, in which he’s making the globe a playground for gangsters.

We used to live in a world where ideologies clashed, but ideologies don’t seem to matter anymore. The strongman understanding of power is on the march. Power is like money: the more the better. Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and the rest of the world’s authoritarians are forming an axis of ruthlessness before our eyes. Trumpism has become a form of nihilism that is devouring everything in its path.

The pathetic thing is that I didn’t see this coming even though I’ve been living around these people my whole adult life. I joined the conservative movement in the 1980s, when I worked in turn at National Review, The Washington Times, and The Wall Street Journal editorial page. There were two kinds of people in our movement back then, the conservatives and the reactionaries. We conservatives earnestly read Milton Friedman, James Burnham, Whittaker Chambers, and Edmund Burke. The reactionaries just wanted to shock the left. We conservatives oriented our lives around writing for intellectual magazines; the reactionaries were attracted to TV and radio. We were on the political right but had many liberal friends; they had contempt for anyone not on the anti-establishment right. They were not pro-conservative—they were anti-left. I have come to appreciate that this is an important difference.

I should have understood this much sooner, because the reactionaries had revealed their true character as far back as January 1986. A group of progressive students at Dartmouth had erected a shantytown on campus to protest apartheid. One night, a group of 12 students, most of them associated with the right-wing Dartmouth Review, descended on the shanties with sledgehammers and smashed them down.

Even then I was appalled. Apartheid was evil, and worth opposing. A nighttime raid with sledgehammers seemed more Gestapo than Burkean. But conservative intellectuals didn’t take this seriously enough. In large part, I think this was because we looked down on the Dartmouth Review mafia, whose members had included Laura Ingraham and Dinesh D’Souza. Their intellectual standards were so obviously third-rate. I don’t know how to put this politely, but they just seemed creepy—nakedly ambitious in a way that I thought would destroy them in the end.

[From the December 2024 issue: David Brooks on how the Ivy League broke America]

Instead, history has smiled on them. A prominent publisher of right-wing authors once told me that the way to sell conservative books is not to write a good book—it’s to write a book that will offend the left, thereby causing the reactionaries to rally to your side and buy it. That led to books with titles such as The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left, and to Ann Coulter’s entire career. Owning the libs became a lucrative strategy.

Of course, the left made it easy for them. The left really did purge conservatives from universities and other cultural power centers. The left really did valorize a “meritocratic” caste system that privileged the children of the affluent and screwed the working class. The left really did pontificate to their unenlightened moral inferiors on everything from gender to the environment. The left really did create a stifling orthodoxy that stamped out dissent. If you tell half the country that their voices don’t matter, then the voiceless are going to flip over the table.

But although Trump may have campaigned as a MAGA populist, leveraging this working-class resentment to gain power, he governs as a Palm Beach elitist. Trump and Elon Musk are billionaires who went to the University of Pennsylvania. J. D. Vance went to Yale Law School. Pete Hegseth went to Princeton and Harvard. Vivek Ramaswamy went to Yale and Harvard. Stephen Miller went to Duke. Ted Cruz went to Princeton and Harvard. Many of Musk’s DOGE workers, according to The New York Times, come from elite institutions—Harvard, Princeton, Morgan Stanley, McKinsey, Wharton. These are the Vineyard Vines nihilists, the spiritual descendants of the elite bad boys at the Dartmouth Review. This political moment isn’t populists versus elitists; it is, as I’ve written before, like a civil war in a prep school where the sleazy rich kids are taking on the pretentious rich kids.

[Derek Thompson: DOGE’s reign of ineptitude]

The MAGA elite rode to power on working-class votes, but—trust me, I know some of them—they don’t care about the working class. Trump and his crew could have taken office with actual plans to make life better for working-class Americans. An administration that cared about the working class would seek to address its problems, such as the fact that the poorest Americans die an average of 10 to 15 years younger than their higher-income counterparts, or that by sixth grade, many of the children in the poorest school districts have fallen four grade levels behind those in the richest. An administration that cared about these people would have offered a bipartisan industrial policy to create working-class jobs.

These faux populists have no interest in that. Instead of helping workers, they focus on civil war with their left-wing fellow elites. During Trump’s first months in office, one of their highest priorities has been to destroy the places where they think liberal elites work—the scientific community, the foreign-aid community, the Kennedy Center, the Department of Education, universities.

It turns out that when you mix narcissism and nihilism, you create an acid that corrodes every belief system it touches.

This Trumpian cocktail has eaten away at Christianity, a faith oriented around the marginalized. Blessed are the meek. Blessed are the poor in spirit. The poor are closer to God than the rich. Again and again, Jesus explicitly renounced worldly power.

[Read: Evangelicals made a bad trade]

But if Trumpism has a central tenet, it is untrammeled lust for worldly power. In Trumpian circles, many people ostentatiously identify as Christians but don’t talk about Jesus very much; they have crosses on their chest but Nietzsche in their heart—or, to be more precise, a high-school sophomore’s version of Nietzsche.

To Nietzsche, all of those Christian pieties about justice, peace, love, and civility are constraints that the weak erect to emasculate the strong. In this view, Nietzscheanism is a morality for winners. It worships the pagan virtues: power, courage, glory, will, self-assertion. The Nietzschean Übermenschen—which Trump and Musk clearly believe themselves to be—offer the promise of domination over those sick sentimentalists who practice compassion.

Two decades ago, Michael Gerson, a graduate of Wheaton College, a prominent evangelical institution, helped George W. Bush start the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, which has saved 25 million lives in Africa and elsewhere. I traveled with Gerson to Namibia, Mozambique, and South Africa, where dying people had recovered and returned to their families, and were leading active lives. It was a proud moment to be an American. Vought—Trump’s budget director, who also graduated from Wheaton—championed the evisceration of PEPFAR, which has now been set in motion by executive order, effectively sentencing thousands to death. Project 2025, of which Vought was a principal architect, helped lay the groundwork for the dismantling of USAID; its gutting appears to have ended a program to supply malaria protection to 53 million people and cut emergency food packages for starving children. Twenty years is a short time in which to have traveled the long moral distance from Gerson to Vought.

[From the April 2018 issue: Michael Gerson on Trump and the evangelical temptation]

Trumpian nihilism has eviscerated conservatism. The people in this administration are not conservatives. They are the opposite of conservatives. Conservatives once believed in steady but incremental reform; Elon Musk believes in rash and instantaneous disruption. Conservatives once believed that moral norms restrain and civilize us, habituating us to virtue; Trumpism trashes moral norms in every direction, riding forward on a tide of adultery, abuse, cruelty, immaturity, grift, and corruption. Conservatives once believed in constitutional government and the Madisonian separation of powers; Trump bulldozes checks and balances, declaiming on social media, “He who saves his Country does not violate any Law.” Reagan promoted democracy abroad because he thought it the political system most consistent with human dignity; the Trump administration couldn’t care less about promoting democracy—or about human dignity.

How does this end? Will anyone on the right finally stand up to the Trumpian onslaught? Will our institutions withstand the nihilist assault? Is America on the verge of ruin?

In February, about a month into Trump’s second term, I spoke at a gathering of conservatives in London called the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship. Some of the speakers were pure populist (Vivek Ramaswamy, Mike Johnson, and Nigel Farage). But others were center-right or not neatly ideological (Niall Ferguson, Bishop Robert Barron, and my Atlantic colleague Arthur C. Brooks).

[David Brooks: Confessions of a Republican exile]

In some ways, it was like the conservative conferences I’ve been attending for decades. I listened to a woman from Senegal talking about trying to make her country’s culture more entrepreneurial. I met the head of a charter school in the Bronx that focuses on character formation. But in other ways, this conference was startlingly different.

In my own talk, I sympathized with the populist critique of what has gone wrong in Western societies. But I shared with the audience my dark view of President Trump. Unsurprisingly, a large segment of the audience booed vigorously. One man screamed that I was a traitor and stormed out. But many other people cheered. Even in conservative precincts infected by reactionary MAGA-ism, some people are evidently tired of Trumpian brutality.

As the conference went on, I noticed a contest of metaphors. The true conservatives used metaphors of growth or spiritual recovery. Society is an organism that needs healing, or it is a social fabric that needs to be rewoven. A poet named Joshua Luke Smith said we needed to be the seeds of regrowth, to plant the trees for future generations. His incantation was beatitudinal: “Remember the poor. Remember the poor.”

But others relied on military metaphors. We are in the midst of civilizational war. “They”—the wokesters, the radical Muslims, the left—are destroying our culture. There were allusions to the final epochal battles in The Lord of the Rings. The implication was that Sauron is leading his Orc hordes to destroy us. We are the heroic remnant. We must crush or be crushed.

The warriors tend to think people like me are soft and naive. I tend to think they are catastrophizing narcissists. When I look at Trump acolytes, I see a swarm of Neville Chamberlains who think they’re Winston Churchill.

I understand the seductive power of a demagogue who tells you that the people who look down on you are evil. I understand the seductive power of being told that your civilization is on the verge of total collapse, and that everything around you is degeneracy and ruin. This message gives you a kind of terrifying thrill: The stakes are apocalyptic. Your life has meaning and urgency. Everything is broken; let’s burn it all down.

I understand why people who feel alienated would want to follow the leader who speaks about domination and combat, not the one who speaks about healing and cooperation. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve read Edmund Burke or the Gospel of Matthew—it’s still tempting to throw away all of your beliefs to support the leader who promises to be “your retribution.”

America may well enter a period of democratic decay and international isolation. It takes decades to develop strong alliances, and to build the structures and customs of democracy—and only weeks to decimate them, as we’ve now seen. And yet I find myself confident that America will survive this crisis. Many nations, including our own, have gone through worse and bloodier crises and recovered. In Upheaval: Turning Points for Nations in Crisis, the historian and scientist Jared Diamond provides case studies—Japan in the late 19th century, Finland and Germany after World War II, Indonesia after the 1960s, Chile and Australia during and after the ’70s—of countries that came back stronger after crisis, collapse, or defeat. To these examples, I’d add Britain in the 1830s and ’40s, and the 1980s, and South Korea in the 1980s. Some of these countries (such as Japan) endured war; others (Chile) endured mass torture and “disappearances”; still others (Britain and Australia) endured social decay and national decline. All of them eventually healed and came back.

America itself has already been through numerous periods of rupture and repair. Some people think we’re living through a period of unprecedented tumult, but the Civil War and the Great Depression were much worse. So were the late 1960s—assassinations, riots, a failed war, surging crime rates, a society coming apart. From January 1969 until April 1970, there were 4,330 bombings in the U.S., or about nine a day. But by the 1980s and ’90s—after getting through Watergate, stagflation, and the Carter-era “malaise” of the ’70s—we had recovered. As brutal and disruptive as the tumult of the late 1960s was, it helped the country shake off some of its persistent racism and sexism, and made possible a freer and more individualistic ethos.

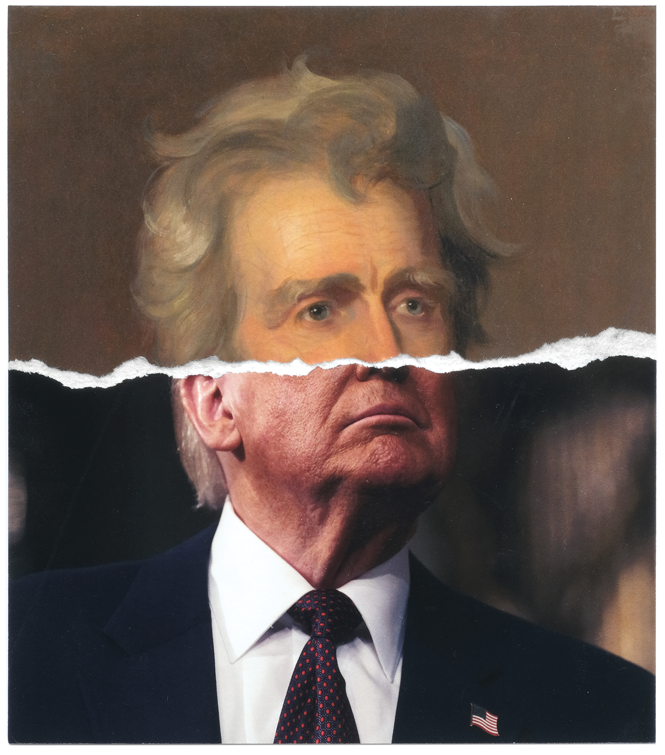

But the most salient historical parallel might be the America of the 1830s. Andrew Jackson is the American president who most resembles Trump—power-hungry, rash, narcissistic, driven by animosity. He was known by his opponents as “King Andrew” for his expansions of executive power. “The man we have made our President has made himself our despot, and the Constitution now lies a heap of ruins at his feet,” Senator Asher Robbins of Rhode Island said. “When the way to his object lies through the Constitution, the Constitution has not the strength of a cobweb to restrain him from breaking through it.” Jackson brazenly defied the Supreme Court on a ruling about Cherokee Nation territory (a defiance, it should be noted, that Vice President Vance has explicitly endorsed). “Though we live under the form of a republic,” Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story wrote, “we are in fact under the absolute rule of a single man.”

But Jackson made the classic mistake of the populist: He overreached. Fueled by personal hostility toward elites, he destroyed the Second Bank of the United States, an early precursor to the Federal Reserve System, and helped spark an economic depression that ruined the administration of his chosen successor, Martin Van Buren.

In response to Jackson, the Whig Party arose in the 1830s to create a new political and social order. Devoutly anti-authoritarian, the Whigs were a cultural, civic, and political force all at once. They emphasized both traditional morality and progressive improvements. They agitated for prison reform and for keeping the Sabbath, for more women’s participation in politics and for a strong military, for government-funded public schools and for pro-business government policies. They were opposed to Jackson’s monstrous Indian Removal Act, and to the Democratic Party’s reactionary, white-supremacist social vision. Whereas Jacksonian Democrats emphasized negative liberty—get your hands off me—the Whigs, who would turn into the early Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln, emphasized positive liberty, empowering Americans to live bigger, better lives with things such as expanded economic credit, free public education, and stronger legal protections including due process and property rights.

Though we’ve come to call the early-to-mid-19th century the Age of Jackson, the historian Daniel Walker Howe notes that it was not Jackson but the Whigs who created the America we know today. “As economic modernizers, as supporters of strong national government, and as humanitarians more receptive than their rivals to talent regardless of race and gender,” Howe writes, the Whigs “facilitated the transformation of the United States from a collection of parochial agricultural communities into a cosmopolitan nation integrated by commerce, industry, information, and voluntary associations as well as by political ties.” Looking back, Howe concludes, we can see that even though they were not the dominant party of their time, the Whigs “were the party of America’s future.” To begin its recovery from Trumpism, America needs its next Whig moment.

Yes, we have reached a point of traumatic rupture. A demagogue has come to power and is ripping everything down. But what’s likely to happen is that the demagogue will start making mistakes, because incompetence is built into the nihilistic project. Nihilists can only destroy, not build. Authoritarian nihilism is inherently stupid. I don’t mean that Trumpists have low IQs. I mean they do things that run directly against their own interests. They are pathologically self-destructive. When you create an administration in which one man has all the power and everybody else has to flatter his voracious ego, stupidity results. Authoritarians are also morally stupid. Humility, prudence, and honesty are not just nice virtues to have—they are practical tools that produce good outcomes. When you replace them with greed, lust, hypocrisy, and dishonesty, terrible things happen.

[From the September 2023 issue: David Brooks on why Americans are so awful to one another]

The DOGE children are doubtless brilliant in certain ways, but they know as much about government as I know about rocketry. They announced an $8 billion cut to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement contract—though if they had read their own documents correctly, they would have realized that the cut was less than $8 million. They eliminated workers from the National Nuclear Security Administration, apparently without realizing that this agency controls nuclear security, and had to undo some of those cuts shortly thereafter. Trump seems to be trying to give a bunch of Sam Bankman-Frieds access to America’s nuclear arsenal and IRS records. What could go wrong?

When Trump creates an unnecessary crisis, it’s unlikely to be a small one. The proverbial “adults in the room” who contained crises in Trump’s first term are gone. Whatever the second-term crisis—runaway inflation? a global trade war? a cratered economy and plummeting stock market? an out-of-control conflict in China? botched pandemic management? a true hijacking of the Constitution precipitated by defiance of the courts?—it is likely to crater his support and shift historical momentum.

But although Trumpism’s collapse is a necessary condition for national recovery, it is not a sufficient one. Its demise must be followed by the hard work necessary to achieve true civic and political renewal.

Progress is not always a smooth or merry ride. For a few decades, nations live according to one paradigm. Then it stops working and gets destroyed. When the time comes to build a new paradigm, progressives talk about economic redistribution; conservatives talk about cultural and civic repair. History shows that you need both: Recovery from national crisis demands comprehensive reinvention at all levels of society. If you look back across the centuries, you find that this process requires several interconnected efforts.

First, a national shift in values. In the late 19th century, for example, as the country went through the wrenching process of industrialization, America was traumatized by severe recessions and mass urban poverty. In response, social Darwinism gave way to the social-gospel movement. Social Darwinism, associated with thinkers such as Herbert Spencer, valorized survival of the fittest and claimed that the poor are poor because of inferior abilities. The social-gospel movement, associated with theologians such as Walter Rauschenbusch, emphasized the systemic causes of poverty, including the Gilded Age’s concentration of corporate power. By the early 20th century, most mainline Protestant denominations had signed on to the Social Creed of the Churches, which called for, among other things, the abolition of child labor and the creation of disability insurance.

Second, nations that hang together through crisis have a strong national identity—they return to their roots. They have a leader who replaces the amoralism of the nihilists, or, say, the immorality of slavery, with a strong redefinition of the nation’s moral mission, the way Lincoln redefined America at Gettysburg.

Third, a civic renaissance. After the social gospel took root, Americans in the 1890s and early 1900s launched and participated in a series of social movements and civic organizations: United Way, the NAACP, the Sierra Club, the settlement-house movement, the American Legion.

Fourth, a national reassessment. As Jared Diamond notes, nations that turn around don’t catastrophize. Rather, they develop a clear-eyed view of what’s working and not working, and they pursue careful, selective change. According to Diamond’s research, the leaders of successful reform movements also take responsibility for their part in the crisis. For instance, Germany’s leaders accepted responsibility for the country’s Nazi past; Finland’s leaders took responsibility for an unrealistic foreign policy before World War II, when they had to deal with a looming Soviet Union on their border; and Australia’s leaders took responsibility in the 1970s for a political culture and foreign policy that had become overly dependent on Britain.

Fifth, a surge of political reform. In 1830s and ’40s Britain—racked by social chaos, bank failures, a severe depression, riots, and crushing wealth inequality—Prime Minister Robert Peel, a leader of great moral rectitude, built the modern police force, reduced tariffs, pushed railway legislation that literally laid the tracks for British industrialization, and helped pass the Factory Act of 1844, which regulated workplaces. In early-20th-century America, Progressives produced a comparable flurry of effective reforms that pulled the country out of its industrialization crisis.

Part of political reform is an expansion of the circle of power. What that would require in America today is, among other things, a broad effort to include working-class and conservative voices in what have traditionally been cultural bastions of elite progressivism—universities, the nonprofit sector, the civil service, the mainstream media.

[Derek Thompson: Abundance can be America’s next political order]

Finally, economic expansion. Economic growth can salve many wounds. Pursuing a so-called abundance agenda—a set of policies aimed at reducing government regulation and increasing investment in innovation, and expanding the supply of housing, energy, and health care—is the most promising way to achieve that expansion.

in the long term, Trumpism is doomed. Power without prudence and humility invariably fails. Nations, like people, change not when times are good but in response to pain. At a moment when Trumpism seems to be devouring everything, the temptation is to believe that this time is different.

But history doesn’t stop moving. Even now, as I travel around the country, I see the forces of repair gathering in neighborhoods and communities. If you’re part of an organization that builds trust across class, you’re fighting Trumpism. If you’re a Democrat jettisoning insular faculty-lounge progressivism in favor of a Whig-like working-class abundance agenda, you’re fighting Trumpism. If you are standing up for a moral code of tolerance and pluralism that can hold America together, you’re fighting Trumpism.

Over time, changes in values lead to changes in relationships, which lead to changes in civic life, which eventually lead to changes in policy and then in the general trajectory of the nation. It starts slow, but as the Book of Job says, the sparks will fly upward.

This article appears in the May 2025 print edition with the headline “Everything We Once Believed In.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?

![[WATCH]Cam’ron Reveals His Family Are The Owners Of California Staple Roscoe’s Chicken And Waffles](https://thesource.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-04-07-at-8.39.39-AM.png)