America Is the Land of Opportunity—For White South Africans

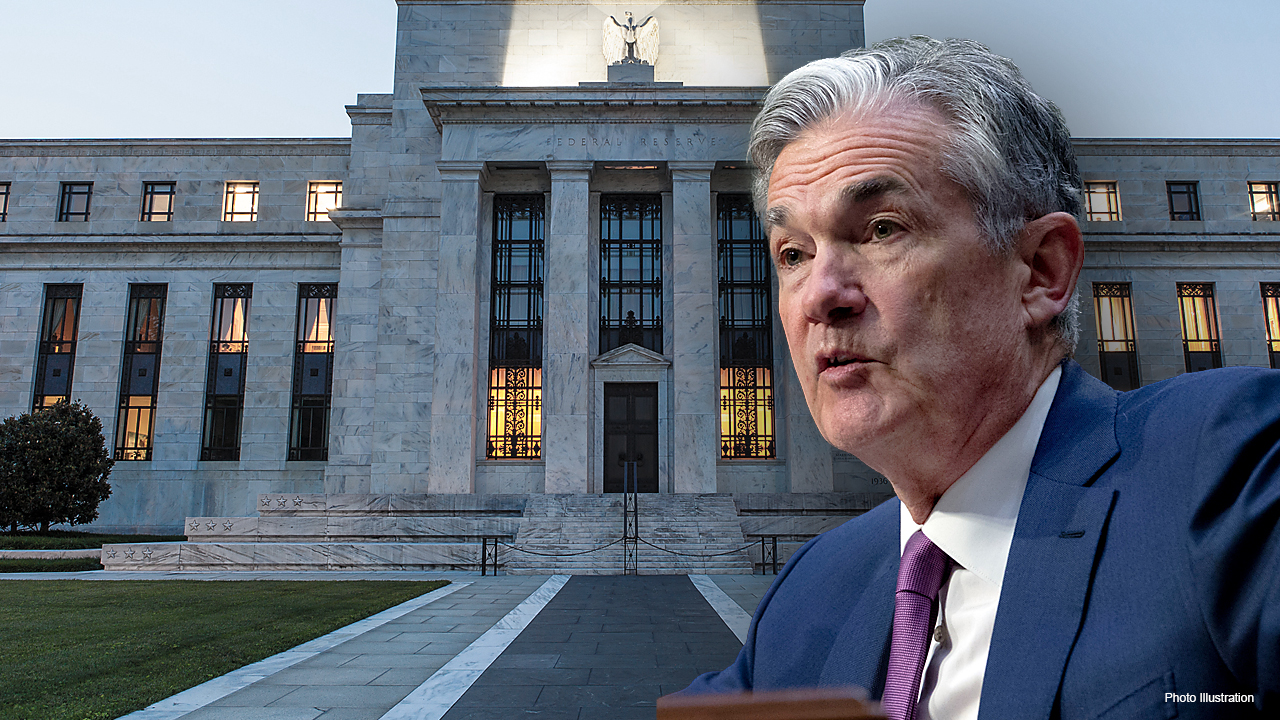

Trump has frozen refugee admissions and cut off resettlement funding, but he has made an exception for white South Africans, who he says are victims of racial discrimination.

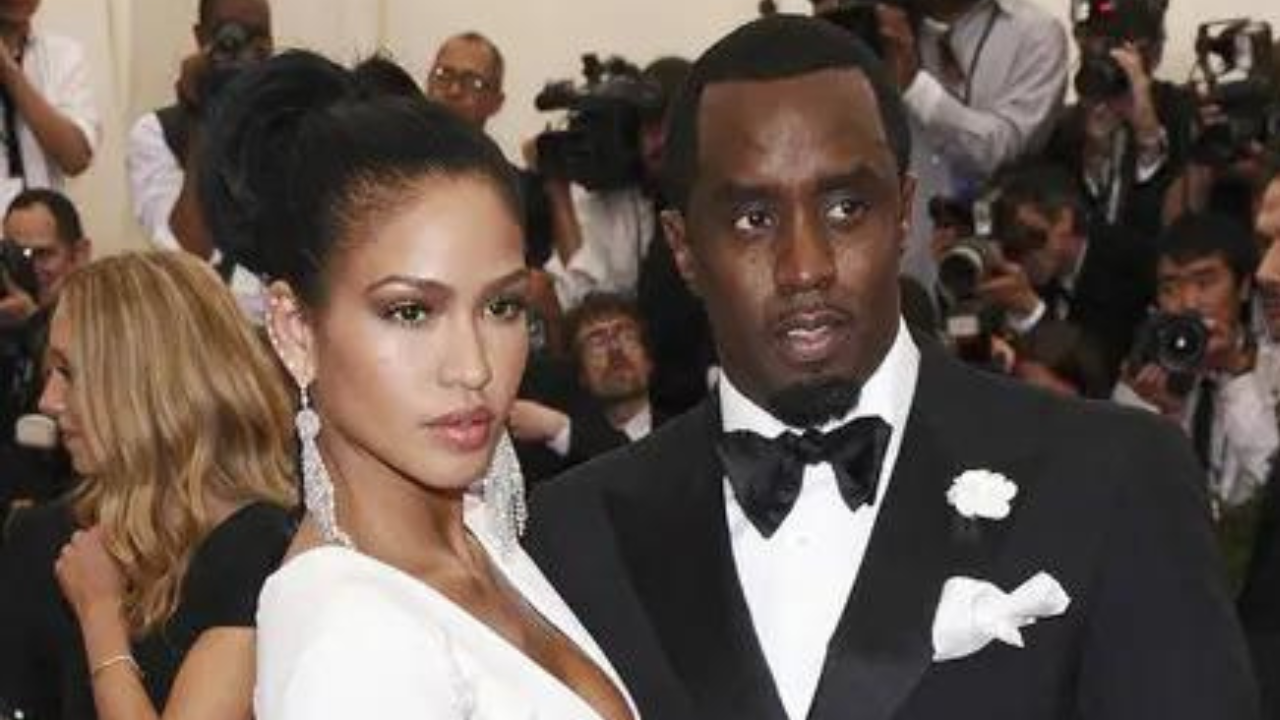

When the welcome ceremony was over, and the Trump officials drove off in their black SUVs, a dozen or so newly arrived South African refugees stepped out into the parking lot of a private terminal at Washington Dulles International Airport yesterday afternoon, still carrying little paper flags they’d been handed. Now it was time for a smoke.

Will Hartzenberg, a tall, sunworn 44-year-old farmer from the Limpopo region in the country’s north, was on his way to Idaho with his family to start a new life. “Relief,” he told me, when asked what he felt. “We are really relieved.”

Hartzenberg said his wife, Carmen, had teased him for worrying whether it was safe to leave their young children inside the building while they stepped out for a cigarette. He needed to learn to let down his guard, he figured. “This is not South Africa, where you have to take your children with you wherever you go,” he said.

A U.S. official came over to hurry the group back into the terminal. They smoked faster. Hartzenberg’s parents and sister had been shot during an attack on the family farm in 1993, he told me as he walked. They survived, but he said he didn’t see a future for his children in South Africa, or at least not a prosperous one.

[Adam Serwer: Afrikaner ‘refugees’ only]

The country’s white minority—descendants of British colonists, and Afrikaners from the Netherlands and other European countries—once dominated South Africa through the apartheid system of legalized discrimination, confining the country’s majority-Black population in slums. Three decades after that system’s defeat, the plight of white South Africans has become a cause célèbre among white-nationalist groups. American President Donald Trump says they are victims of racial discrimination and genocide—claims that South Africa’s government calls “completely false.”

Hartzenberg and his family will be resettled in a state that is 92.5 percent white. When he researched Idaho’s landscapes online, he liked what he saw: “We come from a farm that is surrounded by mountains. So I was quite excited when I Googled to see where we are going.”

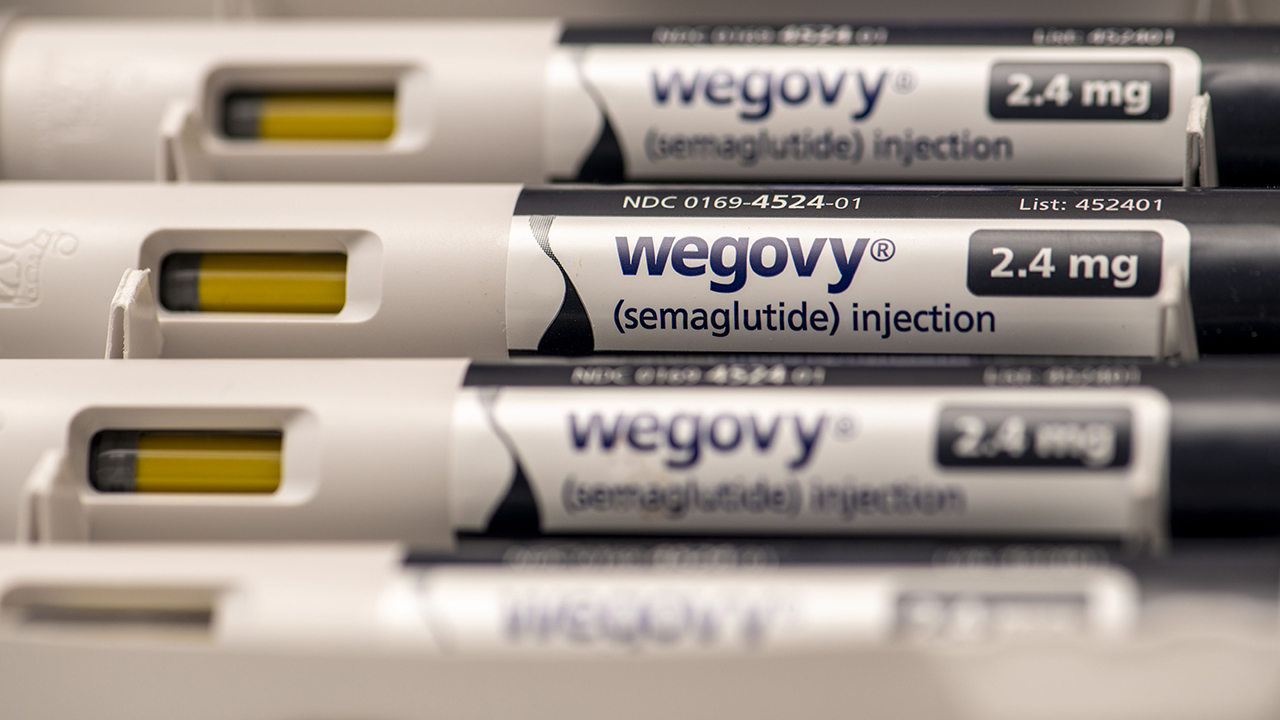

Hartzenberg’s mix of bewilderment, relief, and optimism has been shared by generations of refugees as they set foot in the United States for the first time. Few have enjoyed the kind of support the South Africans are receiving from the Trump administration, which has all but frozen refugee admissions from other nations and cut off resettlement funding. That has stranded at least 12,000 refugees, many from conflict zones, who had flights to the United States booked after they were extensively vetted and approved for resettlement—only to learn that they were no longer welcome in the United States, according to aid groups suing the Trump administration.

One resettlement agency affiliated with the Episcopal Church said yesterday that it will not help resettle the Afrikaners as required under its federal grant. The church’s presiding bishop, Mark Rowe, sent a letter to members of the Church saying it was terminating its four-decade-old partnership with the government. The bishop said Trump’s resettlement plan crossed a moral line for the Church, which is part of the global Anglican Communion and whose leaders have included the late South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

“It has been painful to watch one group of refugees, selected in a highly unusual manner, receive preferential treatment over many others who have been waiting in refugee camps or dangerous conditions for years,” Rowe wrote. They include “brave people who worked alongside our military in Iraq and Afghanistan and now face danger at home because of their service to our country,” he added.

The Trump administration said yesterday that it will end temporary immigration protections for some Afghans who are already in the United States on July 12, leaving about 9,000 immigrants at risk of being deported back to the Taliban-controlled nation.

The White House’s grand welcome for the white refugees came as the Trump administration is waging a deportation campaign, aimed at removing millions of immigrants from the United States. Trump has depicted recent waves of immigrants, particularly from Latin America, as an existential threat to the United States that is “poisoning the blood” of the country.

Hartzenberg and his family and the other refugees were warmly welcomed after their chartered flight landed in northern Virginia around midday. They were greeted by Deputy Homeland Security Secretary Troy Edgar and Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau, who connected their own lives to those of the new arrivals. Landau said his father fled the Nazi takeover in Europe and found safety and freedom in the United States. Edgar told the group his wife is an Iranian Christian who fled persecution in her homeland.

“A lot of you, I think, are farmers, right?” Landau said. “When you have quality seeds, you can put them in foreign soil and they will blossom. They will bloom. We are excited to welcome you here to our country where we think you will bloom.”

Edgar told the South Africans they would receive the officials’ personal contact info—a gesture that seemed to underscore the newcomers’ special status.

Refugees are in a distinct category among U.S. immigrant groups and are selected because they face persecution or harm in their home countries resulting from their race, religion, nationality, political views, or membership in a particular social group. In years past, the United States has welcomed Vietnamese fleeing a Communist takeover, Soviet émigrés, and Christians from across Africa and the Middle East. Refugees submit to a U.S. vetting and screening process, then endure waits that may stretch for years. They arrive with full legal protection and a path to citizenship, and they receive assistance from resettlement organizations, which are generally affiliated with faith groups and have long enjoyed bipartisan political support.

The South Africans were processed by the Trump administration in a matter of weeks. Asked by a BBC reporter why they were fast-tracked into the United States at a time when other admissions from applicants in Afghanistan or war zones are frozen, Landau said Trump had made an exception based on the dire situation in South Africa. He and Edgar took only two questions in the tightly controlled press event (I was not allowed in) and left without speaking to reporters outside.

South Africa has one of the world’s highest crime rates, and land conflicts have fueled violence in rural areas. Crime data show a few dozen white farmers are killed each year, but their deaths account for fewer than 1 percent of the country’s homicides. “Farmers are being killed,” Trump told reporters at the White House yesterday. “They happen to be white. But whether they’re white or Black makes no difference to me; but white farmers are being brutally killed and their land is being confiscated in South Africa.”

During his first term Trump slashed the number of refugees admitted to the lowest levels since the 1980 Refugee Act went into place. He went even further after he retook office this year, issuing an executive order that suspended refugee admissions. But within weeks he made an exception. White South African farmers have protested vigorously against a law adopted in January that allows courts to take land without compensation in some cases. Officials in South Africa say its purpose is to address inequalities that were lethally enforced during decades of apartheid rule. Although white people make up about 7 percent of South Africa’s population, they own about 75 percent of the farmland, according to a South African government land audit.

[George Packer: ‘What about six years of friendship and fighting together?’]

“The South African government has treated these people terribly—threatening to steal their private land and subjected them to vile racial discrimination,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio wrote on social media yesterday.

The Biden administration resettled about 100,000 people last year. None were from South Africa. Now about 8,000 South Africans have expressed interest in applying for U.S. resettlement, according to U.S. officials.

U.S. visa statistics show that South Africans have been coming to the United States in greater numbers to work as temporary farm laborers—often to operate machinery or perform other skilled tasks. More than 15,000 South Africans came on temporary visas to perform farm labor last year, U.S. data show.

Hartzenberg told me his family grew vegetables on their farm in South Africa. He hoped to return to farming in Idaho, he said, but he wasn’t sure what work might be available. The caseworker assigned to his family hadn’t told him yet. With one last draw on his cigarette, he hustled back into the hangar to gather his children and board a bus to a hotel with the others.

What's Your Reaction?