How the Trump Administration Flipped on Kilmar Abrego Garcia

Officials were developing a plan to get him back to the United States. Why did they stop?

At each stage in the political and legal fight over Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s wrongful deportation, the Trump administration has pushed back harder and dug in deeper.

The administration first called Abrego Garcia’s deportation an “administrative error,” then a “clerical error.” The words trivialized the decision to send a man to a maximum-security prison in El Salvador without legal proceedings and in direct violation of a judge’s protective order. Officials insisted that the mistake could not be undone, disregarding a Supreme Court ruling instructing the administration to “facilitate” his return. Now the president and his advisers maintain, almost daily, that Abrego Garcia will never touch American soil again.

[Read: An ‘administrative error’ sends a Maryland father to a Salvadoran prison]

“He’s NOT coming back,” the White House has declared on social media, while repeatedly calling Abrego Garcia a dangerous criminal and a terrorist.

But in the days after the administration first discovered its mistake, instead of trying to foreclose Abrego Garcia’s return, officials looked for ways to bring him home. They puzzled over the fragmentary evidence tying him to gang membership. And they worried about his safety in a prison where he could be targeted for attack.

A lawsuit filed by Abrego Garcia’s family sparked urgent conversations among attorneys at the Departments of State, Justice, and Homeland Security who were involved in formulating the government’s response. Their discussion—which has not been previously reported—reflected serious concerns, at odds with the administration’s later statements, according to two people familiar with the conversations, as well as notes and memos I reviewed. Both people spoke with me on condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter of ongoing litigation.

These conversations show that U.S. officials initially sought to resolve Abrego Garcia’s case quietly and ensure his safety through the conventional diplomatic channels they’ve used in other cases involving a mistaken deportation. This time, though, their efforts were abruptly halted.

Late last month, three days after Abrego Garcia’s family filed its lawsuit over his deportation, government attorneys began discussing how to undo the mistake and bring him back. In their conversations, officials went so far as to float the idea of having the U.S. ambassador to El Salvador make a personal appeal to the country’s president for Abrego Garcia’s return. But first, the State Department’s legal team wanted more information from DHS about his alleged role in the MS-13 gang. The thin evidence supplied in response was met with skepticism from the State Department lawyers. Abrego Garcia, who came to the United States illegally when he was 16 years old, was one of 23 Salvadorans deported on March 15. But his name had not appeared on an internal list of 10 gang members sought by President Nayib Bukele.

Attorneys at DHS had other concerns. They were aware that, six years ago, a judge had granted Abrego Garcia protected status over fears that he could be targeted for violence should he be returned to El Salvador. That protection was still in effect and had been violated by the March 15 deportation. They wanted to know if U.S. diplomats could ask the Salvadoran government to keep him separated from Barrio 18 gang members who had threatened him in the past and might harm him.

But as criticism of the administration over its mishandling of the case spread, White House officials took over the response and began striking a far more strident tone in their public statements. They swiftly turned an admission of bureaucratic error into a political opportunity—a chance to flex executive authority and test the judicial branch’s ability to restrain presidential power. Abrego Garcia’s deportation became far more than just the case of one man; it developed into a measure of whether Donald Trump’s administration can send people—citizens or not—to foreign prisons without due process. All the while, Abrego Garcia has remained in detention in El Salvador, unable to communicate with his lawyers or his family.

White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt denied that there was an initial effort to return Abrego Garcia. “The Administration has always maintained the position that Abrego Garcia was the man we rightfully intended to deport because he is an illegal immigrant and MS-13 gang Member,” she said in a written response to questions, adding that the administration is complying with court orders in the case.

As the Trump administration resists the pressure to change course, legal proceedings continue. A conservative appellate-court judge issued a blistering opinion rejecting the government’s claims last week, and on Tuesday, the Justice Department said for the first time that U.S. officials had engaged in diplomatic negotiations over Abrego Garcia’s status. Abrego Garcia’s lawyers agreed Wednesday to a one-week pause on the case during closed proceedings whose records are under seal.

[Stephen I. Vladeck: What the courts can still do to constrain Trump]

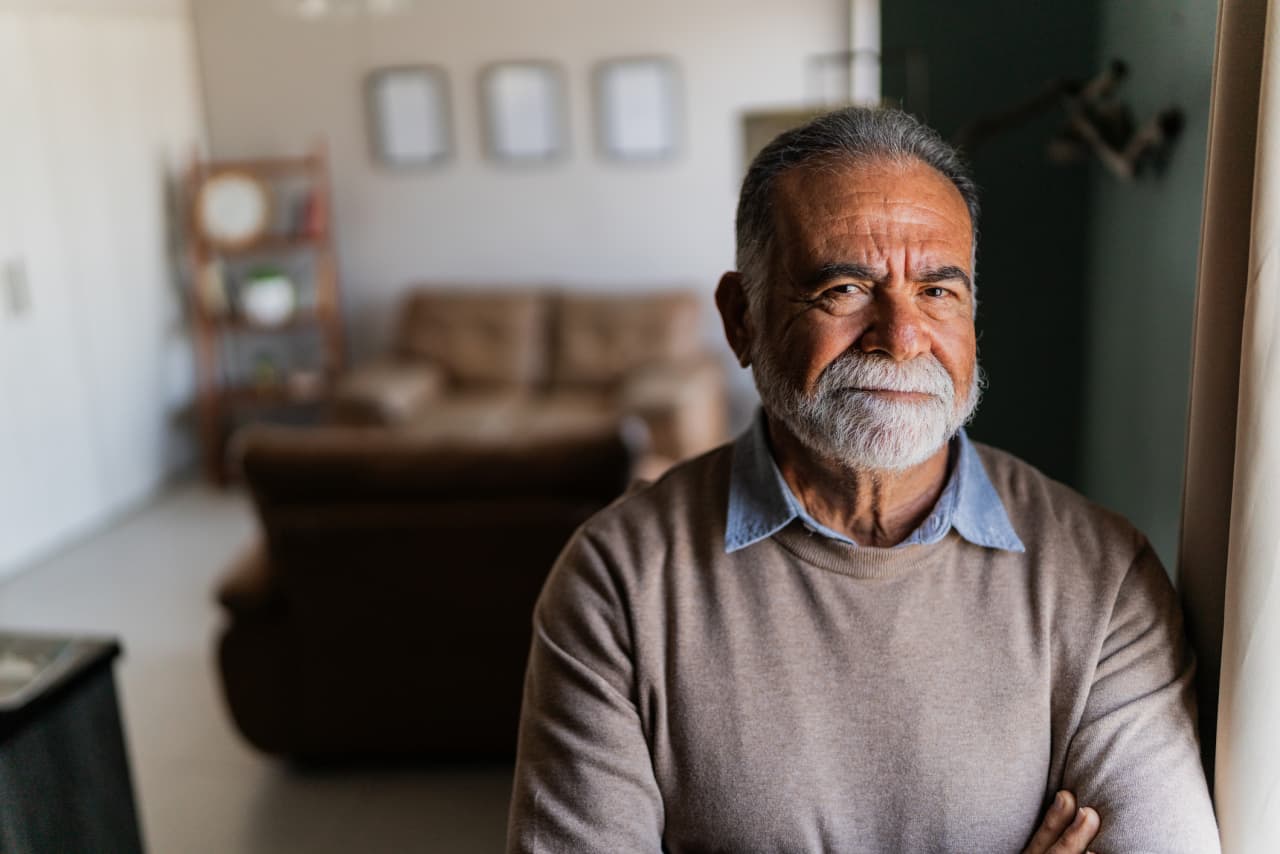

Abrego Garcia, 29, was raising three children with his U.S.-citizen wife and working in construction during his time in the United States. While the administration has depicted him in public statements as a dangerous criminal, judges overseeing the case have chastized the government for not backing their claims with evidence in court.

“The government asserts that Abrego Garcia is a terrorist and a member of MS-13,” Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III, the chief judge of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and a Ronald Reagan appointee, wrote last week. “Perhaps, but perhaps not. Regardless, he is still entitled to due process.”

Some U.S. officials doubted Abrego Garcia’s alleged gang ties from the beginning. In their discussions, State Department officials repeatedly asked DHS and ICE to explain how Abrego Garcia had been identified as an MS-13 member; his possible affiliation with the gang would be a factor in Bukele’s willingness to consider releasing him should the ambassador make a pitch, the officials pointed out. (When Bukele appeared with Trump in the White House on April 14, Bukele called the notion that he would return Abrego Garcia to the United States “preposterous.”)

Abrego Garcia’s record had traffic violations but no criminal charges or convictions. Yet ICE officials told the State Department—falsely—that he had faced criminal charges. They pointed to records showing that Abrego Garcia had been suspected of human or labor trafficking after a traffic stop in Tennessee in 2022. State police had referred the incident to federal authorities because Abrego Garcia had been driving a van with eight passengers from Texas to Maryland. Abrego Garcia had told officers that he was driving the group to a construction job and that the vehicle belonged to his boss. He was cited for driving with an expired license but not charged with human trafficking or any other crime.

ICE said that Abrego Garcia was a member of an MS-13 group called the Western Clique, citing a 2019 report by a gang investigator in Prince George’s County, Maryland. The investigator who filed the report was suspended soon after and charged with misconduct in an unrelated sex-worker case. The document has not been treated as credible by the federal judge overseeing the lawsuit. The Western Clique operates in New York State; Abrego Garcia has never lived there.

An ICE official who provided sworn testimony for a government court filing, Robert Cerna, explained the nature of the error that had mistakenly sent Abrego Garcia back to El Salvador. Abrego Garcia’s protected status had not appeared on the flight manifest for the deportations. Cerna said that Abrego Garcia had been listed as an “alternate”—not one of the original passengers—and moved up the list because other detainees had been taken off the manifest. Under oath, Cerna referred to Abrego Garcia’s “purported membership in MS-13,” but he did not describe him as a confirmed gang member, gang leader, or terrorist.

In 2019, a U.S. immigration judge granted Abrego Garcia withholding of removal, a protected status that prohibited his deportation to El Salvador. The judge found that, should he return, he would likely be targeted by Barrio 18. Abrego Garcia had arrived in the United States in 2011 to join his older brother, and said that he’d fled the Barrio 18 gang that was extorting his mother’s business.

As DHS attorneys scrambled to respond to the lawsuit late last month, they wanted to minimize the government’s liability by seeking to have Abrego Garcia kept away from the gang. But by Monday, March 31, a week after his family filed suit, the Trump administration’s position had begun to harden. In its court filing, the Justice Department acknowledged that Abrego Garcia had been deported as the result of an “administrative error” but said that the government would not take steps to bring him back, arguing that the federal court could not tell the White House how to conduct foreign affairs. One of the Justice Department lawyers who wrote the brief that acknowledged the Trump administration’s error was subsequently fired for, in the words of Attorney General Pam Bondi, not “vigorously” defending Trump.

Leavitt told reporters that Abrego Garcia was a leader of MS-13 who had engaged in human trafficking. Only a few days earlier, government attorneys had discussed how to keep Abrego Garcia safe until they could bring him back. Now the White House was denouncing him as a “terrorist,” saying that he would never return.

As criticism of that stance spread, and federal courts sided against the administration, Vice President J. D. Vance, the Trump adviser Stephen Miller, Bondi, and other top Cabinet officials went on the attack. The White House went from calling Abrego Garcia’s deportation a “clerical error” to insisting that no mistake had been made at all.

Miller, in particular, was determined to use the designation of MS-13 and other criminal groups as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations” to supercharge deportations and bypass standard due-process protections. The White House’s evolving position fit the pattern of Trump’s second term, in which his administration has responded to mistakes by shrugging them off and refusing to take corrective action. Miller took charge of the White House’s messaging, castigating reporters who asked about the case. He also cheered on the administration’s escalating standoff with the judicial branch. After the Supreme Court directed U.S. officials on April 10 to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s return from El Salvador, Miller publicly claimed the opposite: that the Supreme Court had ruled in favor of the White House because the Court had acknowledged the president’s prerogative in managing foreign affairs. (Miller did not respond to a request for comment.)

[Read: Stephen Miller has a plan]

Abrego Garcia was initially sent to the Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT)—a mega-prison from which, the Salvadoran government boasts, no one has ever been released back into society—as part of three planeloads of Venezuelan and Salvadoran detainees. He was transferred out of the facility earlier this month, according to Senator Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, who was allowed to meet with Abrego Garcia last week at a hotel in San Salvador.

Attorneys for the U.S. government said the Bukele administration has told them that Abrego Garcia is being held at a lower-security facility “in good conditions and in an excellent state of health.”

“With respect to any other communications, disclosing any diplomatic discussions regarding Mr. Abrego Garcia could negatively impact any outcome,” the Justice Department said on Monday in a court filing. Attorneys for Abrego Garcia say the Trump administration has the ability to ask for his return because Washington is paying El Salvador at least $6 million each year to imprison detainees sent by the United States. (Van Hollen said he was told that the amount is $15 million.)

“Now that he’s been confirmed healthy,” Bukele wrote on social media last week, “he gets the honor of staying in El Salvador’s custody.”

Jennifer Vasquez Sura, Abrego Garcia’s wife, recently told The Washington Post that she had moved with the couple’s three children to a safe house after DHS posted online a 2021 court document with the family’s address.

Her attorney, Simon Sandoval-Moshenberg, declined on Wednesday to discuss the agreement with the government, citing the court seal. “We remain focused on bringing Kilmar Abrego Garcia home,” he told me in a text message. “We will not rest until he’s brought home.”

*Illustration sources: Alex Wong / Getty; Marvin Recinos / Getty; Win McNamee / Getty; courtesy of the Abrego Garcia family / Reuters.

What's Your Reaction?