The Force That Holds Trump’s Coalition Together

Traditional Republican elites tolerate the authoritarianism because they want the tax cuts.

When I was 5 or 6 years old, I pulled an extremely mean trick on my little brother. I told him that if he cleaned my room, I “might give him a dollar.” Once he had performed the chore, I told him I’d decided against paying him.

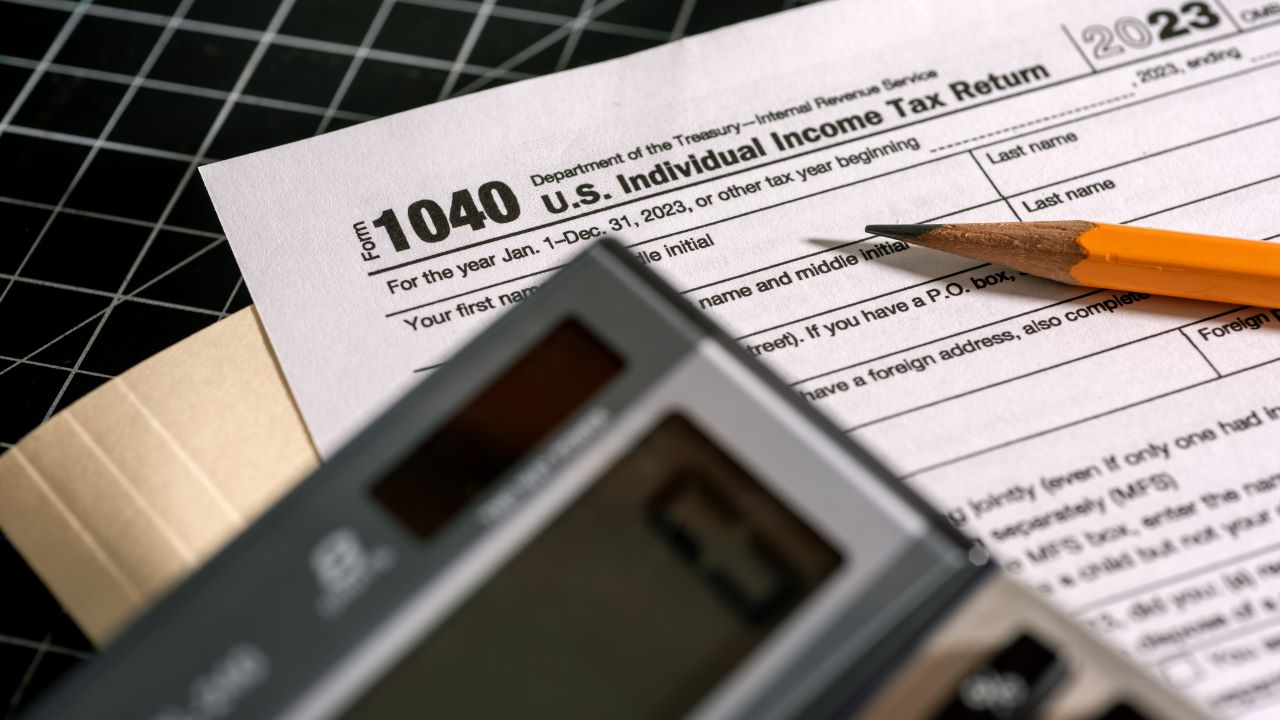

I thought of that shameful (and oddly Trumpian) moment a few weeks ago, when I began encountering news stories reporting that President Donald Trump was considering a plan to raise taxes on the rich. (Axios: “Scoop: Trump might let taxes rise for the rich to cover breaks on tips.” Semafor: “Trump told Republican senators he’s open to raising taxes on highest earners.”) As young children understand when they learn the meaning of words, almost anything might happen. Trump might put Joe Biden’s face on Mount Rushmore. That’s about as likely to happen as him signing into law a hike in the top income-tax rate.

It’s true that a Trump-administration staffer has floated a proposal to do so, and the fact that the president said he was open to it—as he says of nearly every idea lobbed his way—is inherently, if marginally, newsworthy. But the important context missing from the coverage that followed is that Republican politicians promise to raise taxes on the rich routinely. Trump, in fact, said many times during the 2016 campaign that he would raise taxes on people like himself.

[David A. Graham: Trump will never rule out a bad option]

This was reported as a novel break from party orthodoxy at the time. But previous leading Republicans had made similar promises. In 2012, Mitt Romney claimed, “I will not reduce the taxes paid by high-income Americans.” George W. Bush campaigned for his tax cuts in 2001 by citing a single mother earning $22,000 a year as his prototypical beneficiary and suggesting that he intended to level the playing field. (“Somebody struggling to get ahead, somebody working the hardest job in America, pays a higher marginal rate than successful folks, Wall Street bankers. And that’s not right. And that’s not fair.”)

The common thread in all of these statements, including Trump’s, is that they were misleading. Republican politicians seem to understand that reducing taxes for the affluent is unpopular. Their traditional way of overcoming the drag it creates is to obscure their intentions while attempting to win back votes by changing the subject to other topics, such as foreign policy and social issues.

The media tends to forget the slick populist rhetoric of yesteryear, treating each new proclamation as a novel break with party dogma. In 1999, The Washington Post reported that then-candidate Bush’s “emphasis on the poor would mark a clear departure from more traditional conservative GOP tax policy.” Trump similarly drew a spate of friendly press coverage in 2016 about his promise to design a tax plan that would “cost me a fortune,” even though his actual proposal was a traditional regressive tax cut. The mistake is to compare the rhetoric of politicians at a given moment to the policy of politicians in the past. The Republican Party very often promises to do something different from what it used to do. But Republicans in the past promised the same thing.

Some analysts have speculated that the party’s stance really has changed this time, because Republicans have grown more reliant on working-class voters and less reliant on affluent ones. But the GOP obsession with cutting taxes for the rich was never a response to the demands of average Republican voters, very few of whom had any stake in the tax cuts for the ultra-wealthy that obsessed the party’s policy makers.

What has genuinely changed is the addition of a new element to the Republican coalition. The party now includes a national-conservative faction, led by Vice President J. D. Vance. According to the Wall Street Journal opinion writer Kimberly Strassel, the tax leak came from a former Vance staffer. Compared with traditional conservatives, many natcons seem to care more about winning power in order to crush their enemies than to advance specific policy ends. For that reason, they might be more open to raising taxes on the rich: Why risk losing elections over an unpopular policy that isn’t absolutely necessary for their primary goal of owning the libs?

But the natcons have not come particularly close to changing the party’s position on this issue. The reason is that they’re just one faction within the party. The Republican elite still contains a very large wing of traditional, anti-government conservatives. Those economically libertarian conservatives are in tension with the natcons, because they care far more about reducing government (especially government functions that redistribute resources from rich to poor) and have mixed feelings about disappearing people without due process, weaponizing the state against the president’s enemies, fomenting insurrections to overturn election results, and other illiberal methods.

Time after time, however, the traditional conservatives have accepted Trump’s authoritarianism and corruption because he stays loyal to them on their key issues. The path of least resistance for maintaining the coalition is to give each faction what it cares about most: Traditional conservatives get low taxes for the rich (and decreased business regulation), while natcons get a free hand to wield state power against their enemies. This authoritarian-libertarian synthesis might seem ungainly, but it coheres perfectly from the standpoint of those on the right who see progressive taxation and the welfare state as the most sinister threats to liberty.

[Jonathan Chait: A loophole that would swallow the Constitution]

This dynamic is on display in a recent essay by National Review’s Dan McLaughlin attempting to define the American idea. The values he cites include requiring everybody “to abide by the outcomes of the political system” but also “free markets and the right and responsibility of every individual to live off the fruits of his or her own labor and improve his or her own lot in life.” He does not place one above the other, and you can see the tension between the two: What happens if the outcome of the political system is a government that wants to tax rich people? Is the American value to respect the outcome, or ensure that right-wing economic values get to win anyway? McLaughin’s answer is unclear. “The gravest threat to these values,” he writes, “continues to be progressivism and its dissemination through our schools, Hollywood, and the media.” Most anti-government conservatives have reasoned their way into accepting Trump as, at minimum, the lesser of two evils.

Likewise, Randy Barnett, a right-leaning libertarian law professor at Georgetown, posted on X a few days ago a list of “bullets we dodged” by avoiding a Democratic-run government that, he believes, would abolish the filibuster, establish single-payer health care, and fulfill other liberal goals. The president might be claiming the power to whisk any person he chooses to a Central American Gulag without due process, but at least he isn’t doing something as horrific as Medicare for All.

The alliance between the more libertarian faction of the GOP and the natcons has been tested, but not shattered, by Trump’s trade war. Abandoning party doctrine on the sacrosanct issue of taxes would completely sever the bond holding them together. A handful of the president’s allies might float the idea, but you can bet your last dollar it won’t happen.

What's Your Reaction?